Chance News 105

Quotations

Small news item:

“When ants go exploring in search of food they end up choosing collective routes that fit statistical distributions of probability [mixture of Gaussian and Pareto], according to a team of mathematicians who analyzed the trails of a species of Argentine ant. ....”

Submitted by Margaret Cibes

“The problem is simple but daunting. The foundation of opinion research has historically been the ability to draw a random sample of the population. That’s become much harder to do.”

Submitted by Bill Peterson

Forsooth

Statistical Significance.

Definition: A mathematical technique to measure whether the results of a study are likely to be true. Statistical significance is calculated as the probability that an effect observed in a research study is occurring because of chance.

Submitted by Bill Peterson

Italian scientists cleared in Aquila case

“Scientists jailed for manslaughter ... cleared”

Daily Mail.com, November 11, 2014

In 2012 seven Italian scientists were sentenced to 6 years each, and fined a total of about $7 million in damages, because of their “misleadingly reassuring statement” to the people of Aquila just prior to a 6.3 earthquake that resulted in the deaths of 309 people.

Some of the scientists defended their actions in a 2013 Scientific American article

[1].

In 2014 six of them were cleared of all charges, and the seventh, who had claimed that there was “no danger,” had his sentence reduced to two years.

For more about this case, see Chance News 91 and

Chance News 89.

Submitted by Margaret Cibes

Expected value in the NFL

Mike Olinick sent a link to the following:

- N.F.L.explores making the 2-point conversion more tempting

- by Victor Mather, New York Times, 19 May 2015

As football fans know, following a touchdown, the ball is placed at the two-yard line, where a team has the option of either attempting a 1-point kick or a 2-point play from scrimmage. The 2-point option was introduced 20 years ago to make things more interesting, since the kick had become an almost automatic point.

The article gives the success rate for the 2-point play over this 20-year period as 47.5%, compared with 99% for the kick. An easy expected value calculation gives 0.95 points for the 2-point play compared with 0.99 points for the kick. It is not surprising, then, that 2-point attempts have been elected only 5% of the time (typically for strategic reasons involving the difference in scores between the two teams at the time).

The article describes several proposed rule changes that were under consideration to encourage 2-point attempts. As announced here, the final decision was to to move the kick to the 15-yard line, where the estimated success rate is only 90%. (In addition, the defense can score 2 points by returning failed attempts by either method; e.g., blocking a kick or intercepting a pass.)

A fake study on chocolate

Paul Alper sent a link to the following:

- I fooled millions into thinking chocolate helps weight loss. Here's how.

- by John Bohannon, io9.com, 27 May 2015

Publishing under the pseudonym Johannes Bohannon, at his own respectably named website, the Institute of Diet and Health], Bohannon announced the results of a deliberately faulty study designed to show that eating chocolate promotes weight loss. These findings should have sounded too good to be true, but that didn't stop the news and social media outlets from uncritically reporting the findings. The i09.com story linked above includes screen captures from a number of these reports.

The whole story is worth reading for details of how the hoax was conceived and conducted. You can also listen to an NPR interview ("All Things Considered," 29 May 2015). The study used Facebook to recruit a mere 15 volunteers, and randomly assigned them to one of three groups: low carb diet, low carb diet plus a daily chocolate bar, and a control group. Subjects weighed themselves daily, reported on sleep quality and other measures, and had variety of measures taken from blood work, for a total of 18 variables. As Bohannon explains, as long as you don't specify up front what you are looking for, a study with so few subjects and so many variables is bound to turn up a statistically significant result. On ion.com, he calls the design "a recipe for false positives."

Of course, such results will not be reproducible, but the story went viral before anyone asked hard questions. NRP host Robert Siegel wondered if we can take some solace in the fact that reputable sources like the Associated Press or the New York Times did not pick up the story. Bohannon responds that the tabloid press, with its much larger readership, had already done the damage.

For additional perspective on all of this, see What junk food can teach us about junk science (NPR, 8 June 2015).

(See also Chance News 96 for a story of how Bohannon instructively gamed the peer review system.)

Tanzania’s new Statistics Act under fire

The June 2015 issue of Significance magazine contained a brief piece about Tanzania’s new Statistics Act, noting that an up-to-date version of the act was not publicly available at press time. A National Geographic blogger[2] stated that, as of May 13, 2015, there was no official word about whether the president had signed the act.

Nevertheless, a Tanzanian blogger has prepared a 6-page critique of the act -- “The Statistics Act, 2013 – A rapid analysis”, August 4, 2015 [sic] -- in which he discusses his 5 key areas of concern:

1. Uncertainty about who is allowed to generate statistics and what authorization is required

2. Restrictive rules about disseminating survey micro-data

3. Obstacles to whistleblowing without any public interest protections

4. Severe restrictions on the publication or communication of any “contentious” statistical information, and making illegal the publishing/communicating of “false” statistical information or information that “may result in the distortion of facts,” with no protections for acting in good faith

5. Severe penalties for those found guilty of offenses under the bill

For more discussion of potentially problematic aspects of the act, by an English blogger with the adopted Tanzanian name of Mtega[3], see:

“Three (government) statistics that could be illegal under Tanzania’s new Statistics Act”, and

“Four bills later”.

For the act itself, without any 2014 amendments, see: “The Statistics Act, 2013”, United Republic of Tanzania, June 2013.

Submitted by Margaret Cibes

Family income and college prospects

Doulas Rogers alerted us to the following interactive quiz:

- You draw it: How family income predicts children’s college chances

- by Gregor Aisch, Amanda Cox and Kevin Quealy, New York Times, 28 May 2015

Readers are asked to sketch a plot where the vertical axis is the percent of children who attend college and the horizontal axis is the income percentile of their parents. One hint is given: 58 percent of children who were born in the early 1980s and raised in median-income families enrolled in higher education by the time they were 21, so the point (50, 58) is shown on the plot. But readers are free to draw whatever form of a relationship they expect.

To avoid spoilers, you should try on your own before reading further. In a followup article Gauging income and college prospects: How our readers did (2 June) plots the median reader response overlaid with the actual data. (Confession: I missed in exactly the way the authors said was most common).

Also, in A quiet benefit of interactive journalism (6 June), David Leonhardt presents further thoughts on the value of a college education and the public's perception of that value.

A Dilbert forsooth?

Hedging your bets on the God Hypothesis

by Scott Adams, Scott Adams Blog, 3 July 2015

Adams juxtaposes the following two apparently contradictory statistics, presented in a recent article from Business Insider (3 July 2015), which begins, "Although the US might seem more polarized than ever, Americans can still find common ground on plenty or topics."

- 54% of Americans are "very confident" in the existence of a supreme being. (Source: 2014 AP-GfK poll)

- 70% of Americans identify as Christian, although the number has been declining in recent years. (Source: Pew Research Center 2014 Religious Landscape study)

As Adams notes, Christians are presumably a subset of all people who believe in a supreme being.

Discussion

Looking more closely at the survey questions, the AP-GfK asked for degree of confidence in the statement, "The universe is so complex, there must be a supreme being guiding its creation;" whereas Pew asked respondents to self-identity according to religious affiliation. What effect might this have on the results?

Submitted by Bill Peterson

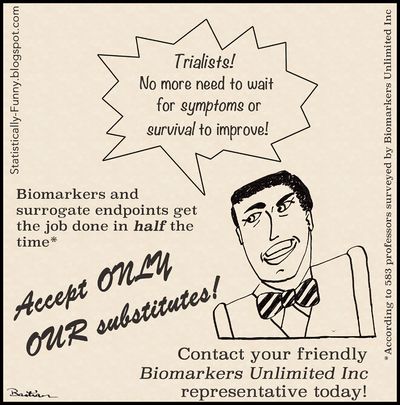

Surrogate markers

Paul Alper sent a link to the following cartoon, from the Statistically funny blog.

There is actually a serious discussion here, and the accompanying text cites viral load in HIV studies as an important example. However,

There is a lot of controversy about surrogate outcomes - and debates about what's needed to show that an outcome or measure is a valid surrogate we can rely on. They can lead us to think that a treatment is more effective than it really is.

Yet a recent investigative report found that cancer drugs are being increasingly approved based only on surrogate outcomes, like "progression-free survival." That measures biomarker activity rather than overall survival (when people died).

Or, quoting Paul on his favorite surrogate marker: "If your car's dashboard light goes on, covering it up with duct tape solves the problem immediately but the car dies at the same time as if you had done nothing."

Does selection bias explain the "hot hand"?

Kevin Tenenbaum sent a link to the following working paper :

- Surprised by the gambler’s and hot hand fallacies? A truth in the law of small numbers

- by Joshua Miller and Adam Sanjurjo, Social Science Research Network, 6 July 2015

The abstract announces, "We find a subtle but substantial bias in a standard measure of the conditional dependence of present outcomes on streaks of past outcomes in sequential data. The mechanism is driven by a form of selection bias, which leads to an underestimate of the true conditional probability of a given outcome when conditioning on prior outcomes of the same kind." The authors give the following simple example to illustrate the bias:

Jack takes a coin from his pocket and decides that he will flip it 4 times in a row, writing down the outcome of each flip on a scrap of paper. After he is done flipping, he will look at the flips that immediately followed an outcome of heads, and compute the relative frequency of heads on those flips. Because the coin is fair, Jack of course expects this conditional relative frequency to be equal to the probability of flipping a heads: 0.5. Shockingly, Jack is wrong. If he were to sample 1 million fair coins and flip each coin 4 times, observing the conditional relative frequency for each coin, on average the relative frequency would be approximately 0.4.

This is a surprising and counterintuitive assertion. To understand what it means, consider enumerating the 16 possible equally likely sequences of four tosses (adapted from Table 1 in the paper).

| Sequence of tosses |

Count of H followed by H |

Proportion of H followed by H |

|---|---|---|

| TTTT | 0 out of 0 | --- |

| TTTH | 0 out of 0 | --- |

| TTHT | 0 out of 1 | 0 |

| THTT | 0 out of 1 | 0 |

| HTTT | 0 out of 1 | 0 |

| HTTT | 0 out of 1 | 0 |

| TTHH | 1 out of 1 | 1 |

| THHT | 1 out of 2 | 1/2 |

| HTTH | 0 out of 1 | 0 |

| HTHT | 0 out of 2 | 0 |

| HHTT | 1 out of 2 | 1/2 |

| THHH | 2 out of 2 | 1 |

| HTHH | 1 out of 2 | 1/2 |

| HHTH | 1 out of 2 | 1/2 |

| HHHT | 2 out of 3 | 2/3 |

| HHHH | 3 out of 3 | 1 |

| TOTAL | 12 out of 24 |

In each of the 16 sequences, only the first three positions have immediate followers. Of course among these 48 total positions, 24 are heads and 24 are tails. For those that are heads, we count how often the following toss is also heads. The sequence TTTT has no heads in the first three positions, so there are no opportunities for a head to follow a head; we record this in the second column as 0 successes in 0 opportunities. The same is true for TTTH. The sequence THHT has two heads in the first three positions; since one is followed by a head and the other by a tail, we record 1 success in 2 opportunities. Summing successes and opportunities for this column gives 12 out of 24, which is no surprise: a head is equally likely to be followed by a head or by a tail. So far nothing is unusual here. This property of independent tosses is often cited as evidence against the hot-hand phenomenon.

But now Miller and Sanjurjo point out the the selection bias inherent in observing a finite sequence after it has been generated: the first flip in a streak of heads will not figure in the proportion of heads that follow a head. Since the overall proportion of heads in the sequence is 1/2, the proportion of heads that follow a head is necessarily less than 1/2. The third column computes for each sequence the relative frequency of a head following a head. This is what the paper calls a "conditional relative frequency", denoted <math>\,\hat{p}(H|H)</math>. The first two sequences do not contribute values. Averaging over the 14 remaining (equally likely) sequences gives (17/3)/14 ≈ 0.4048. This calculation underlies comment above that "the relative frequency would be approximately 0.4". Miller and Sanjurjo go on to provide much more technical analysis, deriving general expressions for the bias in the conditional relative frequencies following streaks of k heads in a sequence of n tosses.

Again quoting from the paper,

The implications for learning are stark: so long as decision makers experience finite length sequences, and simply observe the relative frequencies of one outcome when conditioning on previous outcomes in each sequence, they will never unlearn a belief in the gambler's fallacy.

<\blockquote> That is, people will continue to believe that heads becomes less likely following a run of one or more heads. Moreover, the authors assert that the literature on the "hot hand" has misinterpreted the data:

for those trials that immediately follow a streak of successes, observing that the relative frequency of successes is equal to the base rate of success, is in fact evidence in favor of the hot hand, rather than evidence against it.

The paper was discussed on Andrew Gelman's blog, Hey—guess what? There really is a hot hand! (July 2015). Gelman provides a short R simulation of flipping 1 million fair coins 4 times each, as suggested in the example, and validates the result. (Thanks to Jeff Witmer for posting this reference on the Isolated Statisticians list).

Discussion

What do you make of the last assertion quoted above? If, in a long (rather than fixed length) shot history, the relative frequency of successes is in fact equal to the base rate of success, is this evidence for the hot hand?