Chance News 103

Quotations

"[T]he Law of Large Numbers works … not by balancing out what's already happened, but by diluting what's already happened with new data, until the past is so proportionally negligible that it can safely be forgotten." [p. 74]

"'I've been in a thousand arguments over this topic [hot hand],' [Amos Tversky] said. 'I've won them all, and I've convinced no one.'" [p. 127]

"The significance test is the detective, not the judge." [p. 161]

"Correlation is not transitive. …. Niacin is correlated with high HDL, and high HDL is correlated with low risk of heart attack, but that doesn't mean that niacin prevents heart attacks." [p. 342]

Submitted by Margaret Cibes

“Best, Smith, and Stubbs (2001)[1] found a positive relationship between perceived scientific hardness of psychology journals and the proportion of area devoted to graphs. It is interesting that Smith et al. (2002)[2] found an inverse relationship between area devoted to tables and perceived scientific hardness.”

Submitted by Margaret Cibes

Note. In fact, regarding this last quote, if A is positively correlated with B and B is positively correlated with C, it is possible that A is negatively correlated with C. See Is the property of being positively correlated transitive? (The American Statistician, Vol. 55, No. 4, Novmeber, 2001). Thanks to Paul Alper for this link.

Forsooth

Cancer and luck

Cancer’s random assault

By Denise Grady, New York Times, 5 January 2015

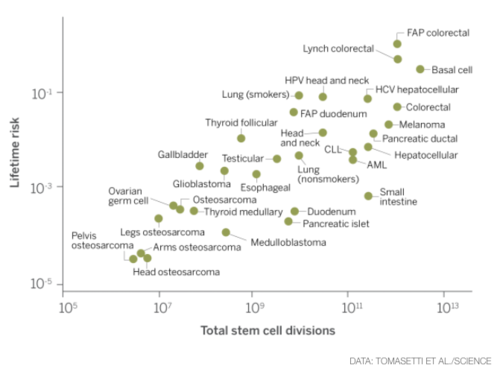

The article concerns a recent research paper, Variation in cancer risk among tissues can be explained by the number of stem cell divisions (Science 2 January 2015). From the abstract

Here, we show that the lifetime risk of cancers of many different types is strongly correlated (0.81) with the total number of divisions of the normal self-renewing cells maintaining that tissue’s homeostasis. These results suggest that only a third of the variation in cancer risk among tissues is attributable to environmental factors or inherited predispositions.

News coverage has created controversy by summarizing the findings in more colloquial terms, similar to this from the NYT article:

Random mutations may account for two-thirds of the risk of getting many types of cancer, leaving the usual suspects — heredity and environmental factors — to account for only one-third, say the authors, Cristian Tomasetti and Dr. Bert Vogelstein, of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

Of course, saying that two-thirds of the variation among cancer types is "explained" by the rate of cell division is not the same thing as saying that two-thirds of risk of a particular cancer is can be accounted for by chance, or that two-thirds of cancer cases are attributable to bad luck. But versions these latter interpretations have appeared in the media.

The resulting controversy is addressed in

- Bad luck and cancer: A science reporter’s reflections on a controversial story

- by Jennifer Couzin-Frankel, Science Insider, 13 January 2015

This article presents the following data graphic of the relationship

We now see where the two-thirds comes from: if the correlation coefficient <math>r = 0.81</math>, as noted in the abstract above, then <math>R^2=0.66</math>.

In response to the controversy, Drs. Tomasetti and Vogelstein (the study's authors), offered some clarifying remarks in an addendum to the original Johns Hopkins news release. In particular, they construct an analogy with driving a car: the road conditions correspond to environmental factors, and the condition of your car to hereditary factors; the length of the trip corresponds to the number of cell divisions; and the risk of having an a accident corresponds to the risk of getting cancer. It makes sense that for any combination of car and road conditions, your risk of an accident increases with the length of the trip. Nevertheless, the authors are careful to note that this does not imply that you should routinely neglect to service your vehicle or or to intelligently plan your route.

Discussion

1. The original headline of the news release was "Bad Luck of Random Mutations Plays Predominant Role in Cancer, Study Shows." Do you think this could have contributed to the misinterpretations? Can you suggest another wording?

2. Consider the same questions for the NYT headline.

Submitted by Bill Peterson

How not to describe a CI

Jeff Witmer sent the following example to the Isolated Statisticans e-mail list, with the subject line "Bayesians at NOAA?" It comes from an NOAA page explaining how to understand uncertainty in climate reports. The context was the recent announcement that 2014 was the warmest year on record (see, for example 2014 breaks heat record, challenging global warming skeptics, New York Times, 16 January 2015).

The plus/minus numbers, which are presented in the data tables of the monthly and annual Global State of the Climate reports, indicate the range of uncertainty (or "range") of the reported global temperature anomaly. For example, a reported global value of +0.69°C ±0.09°C indicates that the most likely value is 0.69°C warmer than the long-term average, but, conservatively, one can be confident that it falls somewhere between 0.60°C and 0.78°C above the long-term average. More technically, it is 95% likely that the value falls within this range. The chance of the actual value being at or beyond the range on the warm side is 2.5% (one in forty chance). Likewise, the chance of the actual value being at or beyond the cool end of the range is 2.5% (one in forty chance).

On a related note, the article Playing Dumb on Climate Change (by Naomi Orestes, New York Times, 5 January 2015) gives a parallel misinterpretation of a p-value.

Typically, scientists apply a 95 percent confidence limit, meaning that they will accept a causal claim only if they can show that the odds of the relationship’s occurring by chance are no more than one in 20. But it also means that if there’s more than even a scant 5 percent possibility that an event occurred by chance, scientists will reject the causal claim.