Chance News 83

Quotations

“A poll is not laser surgery; it’s an estimate.”

ABC Blogs, December 3, 2007

Submitted by Margaret Cibes

"The most famous result of Student’s experimental method is Student’s t-table. But the real end of Student’s inquiry was taste, quality control, and minimally efficient sample sizes for experimental Guinness – not to achieve statistical significance at the .05 level or, worse yet, boast about an artificially randomized experiment."

(Ziliak is the co-author of The Cult of Statistical Significance: How the Standard Error Costs Us Jobs, Justice, and Lives)

Submitted by Bill Peterson

“[W. S. Gossett] wrote to R. A. Fisher of the t tables, "You are probably the only man who will ever use them (Box 1978)."

“[W]e see the data analyst's insistence on ‘letting the data speak to us’ by plots and displays as an instinctive understanding of the need to encourage and to stimulate the pattern recognition and model generating capability of the right brain. Also, it expresses his concern that we not allow our pushy deductive left brain to take over too quickly and perhaps forcibly produce unwarranted conclusions based on an inadequate model.”

Technometrics, February 1984

Thomas L. Moore recommended this article in an ISOSTAT posting. (It is available in JSTOR.)

We are familiar with George Box’s famous statement: “Essentially, all models are wrong., but some are useful.”

Here is another variant, cited in Wikipedia:

“Remember that all models are wrong; the practical question is how wrong do they have to be to not be useful.”

Submitted by Margaret Cibes

Forsooth

“In the first four months [at the new Resorts World Casino New York City], roughly 25,000 gamblers showed up every day, shoving a collective $2.3 billion through the slots and losing $140 million in the process. …. Resorts World offers more than 4,000 slot machines, but thanks to state law, there are no traditional card tables.”

The Wall Street Journal, February 18, 2012

Submitted by Margaret Cibes

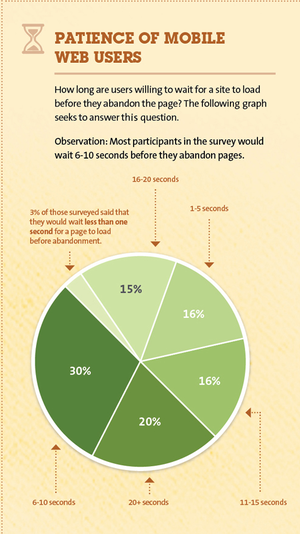

originally cited in “Mobile vs. Desktop”, KISSmetrics

Submitted by Margaret Cibes

“Here is the rub: Apple is so big, it’s running up against the law of large numbers. Also known as the golden theorem, with a proof attributed to the 17th-century Swiss mathematician Jacob Bernoulli, the law states that a variable will revert to a mean over a large sample of results. In the case of the largest companies, it suggests that high earnings growth and a rapid rise in share price will slow as those companies grow ever larger.”

The New York Times, February 24, 2012

Bill Peterson found Andrew Gelman’s comments[1] about this article.

Submitted by Margaret Cibes

Kaiser Fung on Minnesota’s ramp meters

A number references to Kaiser Fung’s book, Numbers Rule Your World, appear in Chance News 82. From a Minnesotan’s point of view, however, the most important topic he discusses is not hurricanes, not drug testing, and not bias in standardized testing. Rather, the most critical issue is ramp metering as a means of improving traffic flow, relieving congestion and reducing travel time on Minnesota highways. “Industry experts regard Minnesota’s system of 430 ramp meters as a national model.”

Unfortunately, “perception trumped reality.” An influential state senator, Dick Day, now a lobbyist for gambling interests, “led a charge to abolish the nationally recognized program, portraying it as part of the problem, not the solution.”

Leave it to Senator Day to speak the minds of “average Joes”--the people he meets at coffee shops, county fairs, summer parades, and the stock car races he loves. He saw ramp metering as a symbol of Big Government strangling our liberty.

In the Twin Cities, drivers perceived their trip times to have lengthened [due to the ramp meters] even though in reality they have probably decreased. Thus, when in September 2000, the state legislature passed a mandate requiring MnDOT [Minnesota Department of Transportation] to conduct a “meters shutoff” experiment [of six weeks], the engineers [who devised the metering program] were stunned and disillusioned.

To make a long story short, when the ramp meters came back on, it turns out that:

[T]he engineering vision triumphed. Freeway conditions indeed worsened after the ramp meters went off. The key findings, based on actual measurements were as follows:

- Peak freeway volume dropped by 9 percent.

- Travel times rose by 22 percent, and the reliability deteriorated.

- Travel speeds declined by 7 percent.

- The number of crashes during merges jumped by 26 percent.

“The consultants further estimated that the benefits of ramp metering outweighed costs by five to one.” Nevertheless, the-above objective measures had to continue to battle subjective ones:

Despite the reality that commuters shortened their journeys if they waited their turns at the ramps, the drivers did not perceive the trade-off to be beneficial; they insisted that they would rather be moving slowly on the freeway than coming to a standstill at the ramp.

Accordingly, the engineers decided to modify the optimum solution to take into account driver psychology. “When they turned the lights back on, they limited waiting time on the ramps to four minutes, retired some unnecessary meters, and also shortened the operating hours.” Said differently, the constrained optimization model the engineers first considered left out some pivotal constraints.

Discussion

1. Do a search for “behavioral economics” to see the prevalence of irrational perceptions and subjective calculations in the economic sphere.

2. Fung discusses an allied, albeit inverse, problem of waiting-time misconception. This instance concerns Disney World and its popular so-called FastPass as a means of avoiding queues. According to Fung

Clearly, FastPass users love the product--but how much waiting time can they save? Amazingly, the answer is none; they spend the same amount of time waiting for popular rides with or without FastPass!..So Disney confirms yet again that perception trumps reality. The FastPass concept is an absolute stroke of genius; it utterly changes perceived waiting times and has made many, many park-goers very, very giddy.

3. An oft-repeated and perhaps apocryphal operations research/statistics/decision theory anecdote has to do with elevators in a very large office building. Employees complained about excessive waiting times because the elevators all too frequently seemed to be in lockstep. Any physical solution such as creating a new elevator shaft or installing a complicated timing algorithm would be very expensive. The famous and utterly inexpensive psychological solution whereby perception trumped reality was to put in mirrors so that the waiting time would seem less because the employees would enjoy admiring themselves in the mirrors. Note that older and more benighted operations research/statistics/decision theory textbooks would have used the word “women” instead of “employees” in the previous sentence.

4. A very modern and frustrating example of perception again trumping reality can often be observed in supermarkets which have installed self-checkout lanes without placing a limit on the number of items per shopper. In order to avoid a line at the regular checkout, some shoppers with an extremely large number of items will often choose the self-checkout and take much longer to finish than if had they queued at the regular checkout. Explain why said shoppers psychologically might prefer to persist in that behavior despite evidence to the contrary. Why don’t supermarkets simply limit the number of items per customer at self-checkout lanes?

Submitted by Paul Alper

Don’t forget Chebyshev

Super Crunchers, by Ian Ayres, Random House, 2007

When I taught at Stanford Law School, professors were required to award grades that had a 3.2 mean. …. The problem was that many of the students and many of the professors had no way to express the degree of variability in professors’ grading habits. …. As a nation, we lack a vocabulary of dispersion. We don’t know how to express what we intuitively know about the variability of a distribution of numbers. The 2SD [2 standard-deviation] rule could help give us this vocabulary. A professor who said that her standard deviation was .2 could have conveyed a lot of information with a single number. The problem is that very few people in the U.S. today understand what this means. But you should know and be able to explain to others that only about 2.5 percent of the professor’s grades are above 3.6. [pp. 221-222]

Discussion

1. Suppose that a professor's awarded grades had mean 3.2 and SD 0.2.

(a) Under what condition could we say that “only about 2.5 percent of the professor’s grades are above 3.6”?

(b) Without that condition, what could we say, if anything, about the percent of awarded grades outside of a 2SD range about the mean? About the percent of awarded grades above 3.6?

2. Suppose that a professor's raw grades had mean 3.2 and SD 0.2. Do you think that this would be a realistic scenario in most undergraduate college classes? In most graduate-school classes? Why or why not?

3. How could a professor construct a distribution of awarded grades with mean 3.2 and SD 0.2, based on raw grades, so that one could say that only about 2.5 percent of the awarded grades are above 3.6? What effect, if any, could that scaling have had on the worst – or on the best – raw grades?

Submitted by Margaret Cibes