Chance News 15

Quotation

Take statistics. Sorry, but you'll find later in life that it's handy to know what a standard deviation is.

New York Times, March 2, 2006

This appears on a list of core knowledge that Brooks says will be sufficient to give you a great education even if you don't make Harvard.

Forsooth

From the February 2006 RSS news we have:

One primary school in East London has a catchment area of 110 metres.

23 October 2005

More on medical studies that conflict with previous studies

Humans, being what they are, it is only natural that when a study's consequences seem plausible there is no need to look too closely. On the other hand, when the outcomes go against what was expected, a great deal of inspection is called for. This was discussed here.

The Wall Street Journal of February 28, 2006 details possible reasons for why the Women's Health Initiative might have had design flaws leading to "murky results." In summary, the WSJ reported:

- Calcium/Vitamin D study

- Message: Supplements don't protect bones or cut risk of colorectal cancer.

- Problem: Those in placebo group also took supplements in many cases.

- Message: Supplements don't protect bones or cut risk of colorectal cancer.

- Low-fat diet study:

- Message: Doesn't cut risk of breast cancer.

- Problem: Few met the fat goal.

- A 22% drop in risk for women who cut fat the most got little emphasis.

- Message: Doesn't cut risk of breast cancer.

- Hormone study:

- Message: No benefit, possible increased cancer and heart risk.

- Problem: Most in study were too old for this to apply to menopausal women.

- Message: No benefit, possible increased cancer and heart risk.

More generally, according to the WSJ, "Design problems in all of the trials mean the results don't really answer the questions they were supposed to address. And a flawed communications effort led to widespread misinterpretation of results by the news media and public."

In particular, in order to reduce the number of participants for the studies, "more than half [of the women] took part in at least two of them, and more that 5,000 were in all three trials." As might be imagined, "Among problems this posed was simple burnout" which "contributed to compliance problems that plagued all three and hurt the reliability of their results."

Another problem was the difficulty of double blinding for the hormone study since any hot flashes would indicate to the patient (and to her physician) that she was in the placebo arm; to get around this impediment, the vast majority of the women recruited were well past menopause, thus biasing the results against the benefits of hormone replacement.

So where are we after 68,132 female participants, "fifteen years and $725 million later"? More than likely, the Women's Health Initiative study will be in and out of the news for some time to come because of its ambiguity.

Submitted by Paul Alper

The economists analyze the tv show "Deal or No Deal?"

Deal or No Deal? Decision making under risk in a large-payoff game show

Thierry Post, Marijn Van den Assem, Guido Baltussen,Richard Thaler

February 2006

The authors of this papere write:

The popular television game show "Deal or No Deal" offers a uniue opportunity for analyzing decision making under risk: it involves very large and wide-ranging stakes, simple sop-go decisions that reuire minimal skill, knowledge or strategy and near-certaint aboutthe probability distribution.

Here is a nice description of the game from the MS Math in the Media magazine:

- Twenty-six known amounts of money, ranging from one cent to one million dollars, are (symbolically) randomly placed in 26 numbered, sealed briefcases. The contestant chooses a briefcase. The unknown sum in the briefcase is the contestant's.

- In the first round of play, the contestant chooses 6 of the remaining 25 briefcases to open. Then the "banker" offers to buy the contestant's briefcase for a sum based on its expected value, given the information now at hand, but tweaked sometimes to make the game more interesting. The contestant can accept ("Deal") or opt to continue play ("No Deal").

- If the game continues, 5 more briefcases are opened in the second round, another offer is made, and accepted or refused. If the contestant continues to refuse the banker's offers, subsequent rounds open 4, 3, 2, 1, 1, 1, 1 briefcases until only two are left.

- The banker makes one last offer; the contestant accepts that offer or takes whatever money is in the initially chosen briefcase.

Thus the banker is always trying to buy out the player. If he fails the player will end up with the amount in suitcase.

The best way to understand the game is to play it here on the NBC website.

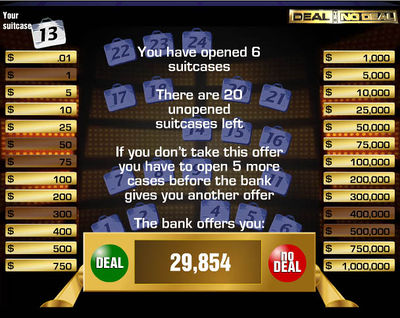

We did this and played the first round. We chose number 13 for our briefcase. Our instruction was to choose six briefcases. We chose suitcases 3,10,12,13,19,25. Here is the result of this round:

The banker has offered us $29.854 to quit. Our six choices eliminated the amounts 1,50,75,300,400,000,500,000. The expected value of our suitcase is now the average of the amounts in the remaining suitcases. Making this calculation we find that the expected value of the amount in our suitcase is $125,900 so we would have to be pretty risk adverse to accept the bankers offer at this point.

We played a second game all the way through and found the following expected values and banker's offers:

Round |

Epected Value |

Offer |

1 |

130,857 |

30565 |

2 |

142,475 |

37361 |

3 |

125,186 |

54507 |

4 |

153,319 |

57554 |

5 |

170,967 |

67160 |

6 |

205,160 |

108950 |

7 |

256,425 |

176781 |

8 |

341,800 |

317700 |

9 |

512,500 |

367500 |

We note that in this case the banker's offer we less than the expected value for all rounds. However, as we get towards the end the decision to accept the offer or not is not so obvious. For example, after the 8th round the only amounts available were $400, $25,000, $1,000,000. I can accept the offer of $317,700 which is a pretty nice amount of money or not accept it and having a 2/3 chance to ending up with a relatively small amount and a 1/3 chance of getting the million dollars. At this kind of choice participants are apt to appear to be risk adverse.