Chance News 101

Quotations

“It is easy to lie with statistics. It is hard to tell the truth without it.”

Submitted by Margaret Cibes

“Recently, I tried ‘treeing out’ (as the decision buffs put it) the choice [my patient] faced. …. When all the possibilities and consequences were penciled out, my decision tree looked more like a bush.”

Submitted by Margaret Cibes

From Significance, July 2014:

“Access to large databases does not reduce the need to understand why these particular samples are available.” (original emphasis)

“[In the early 1970s] I would be called to the bedside of a woman in labour; and instead of asking myself what was the best treatment for her I would find myself asking ‘Who is this woman’s consultant?’ Because all the consultants had their own favoured treatments and responses, whatever I suggested had to fit in which each of them. Nor was it evidence-based decision-making: it was eminence-based decision-making….” (emphasis added)

Note: British Clinician Archie Chalmers created the Cochrane Collaboration in early 1993 to provide medical workers with easily accessible/readable summaries of all clinical trials on various treatments. Hear a half-hour BBC radio interview with Chalmers here.

Submitted by Margaret Cibes

Forsooth

From Naked Statistics, by Charles Whelan, 2013

“Every fall, several Chicago newspapers and magazines publish a ranking of the ‘best’ high schools in the region. …. Several of the high schools consistently at the top of the rankings are selective enrollment schools …. One of the most important admissions criteria is standardized test scores. So let’s summarize: (1) these schools are being recognized as ‘excellent’ for having students with high test scores; (2) to get into such a school, one must have high test scores. This is the logical equivalent of giving an award to the basketball team for doing such an excellent job of producing tall students.”

“[T]he most commonly stolen car is not necessarily the kind of car that is most likely to be stolen. A high number of Honda Civics are reported stolen because there are a lot of them on the road; the chances that any individual Honda Civic is stolen … might be quite low. In contrast, even if 99 percent of all Ferraris are stolen, Ferrari would not make the ‘most commonly stolen’ list, because there are not that many of them to steal.”

“What became known as Meadow’s Law – the idea that one infant death is a tragedy, two are suspicious and three are murder – is based on the notion that if an event is rare, two or more instances of it in the same family are so improbable that they are unlikely to be the result of chance. Sir Roy [Meadow in 1993] told the jury in one of these cases that there was a one in 73m chance that two of the defendant's babies could have died naturally. He got this figure by squaring 8,500—the chance of a single cot death in a non-smoking middle-class family—as one would square six to get the chance of throwing a double six.” [footnote: “The Probability of Injustice”, Economist, January 22, 2004]

“John Ioannidis, a Greek doctor and epidemiologist, examined forty-nine studies published in three prominent medical journals [footnote: “Contradicted and Initially Stronger Effects in Highly Cited Clinical Research”, JAMA, July 13, 2005] …. Yet one-third of the research was subsequently refuted by later work. …. Dr. Ioannidis estimates that roughly half of the scientific papers published will eventually turn out to be wrong. His research was published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, one of the journals in which the articles he studied had appeared. This does create a certain mind-being irony. If Dr. Ioannidis’s research is correct, then there is a good chance that his research is wrong.” (emphasis added)

Submitted by Margaret Cibes

"Gates...found his ratio. 'In general,' he concluded, 'best results are obtained by introducing recitation after devoting about 40 percent of the time to reading. Introducing recitation too early or too late leads to poorer results.' The quickest way to master that Shakespearean sonnet, in other words, is to spend the first third of your time memorizing it and the remaining two-thirds of the time trying to recite it from memory."

How about flunking exams on percents and fractions?

Submitted by Bill Peterson

Submitted by Paul Alper

Atlanta cheating scandal

“Are drastic swings in CRCT scores valid?”

by John Perry and Heather Vogell, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution

Updated July 5, 2011 from original post October 19, 2009

The trial of school employees allegedly involved in a widespread cheating scandal is underway in Georgia with respect to the Criterion-Referenced Competency Tests (CRCT) in some Atlanta schools. Charges stem from student test results that showed “extraordinary gains or drops in scores” between spring of 2008 and 2009. There are about a dozen defendants in this trial; a number of others have accepted plea agreements or received postponements. (See the formal indictment.)

In West Manor and Peyton Forest elementary schools, for instance, students went from among the bottom performers statewide to among the best over the course of one year [on average]. The odds of making such a leap were less than 1 in a billion.

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution conducted a study of average grade-level scores in reading, math and language arts for students in grades 3 to 5. It found that Peyton Forest School had an average math score that rose from among the lowest in the state for 2008 third-graders to fourth in the state for 2009 fourth-graders (a gain of over 6 standard deviations). It also noted that the fourth-graders had scored at the lowest level on math practice tests administered two months before the actual tests in 2009. (The newspaper’s general methodology is described at the end of the article.)

The study also found that West Manor School’s statewide math ranking rose from 830 for fourth-graders in 2008 to the highest statewide for fifth-graders in 2009. The average score had risen by nearly 90 points year to year (a gain of over 6 standard deviations), compared the statewide average rise of about 15 points. Similarly, the gain in average score from practice test to actual test in 2009 was highly unusual.

A third school’s results showed results in the opposite direction with respect to average writing scores – from the top statewide average score for fourth-graders in 2008 to an extremely low average score for fifth-graders in 2009.

Two common aspects of a statistical analyses of average scores are erasure marks - with an unusual number of answers changed from incorrect to correct - and unexpected patterns of responses - with students getting more hard than easy questions correct. State investigators found strong evidence of the former in the Atlanta schools.

A district spokesman has offered some "explanations": some schools might teach their curricula differently, the changes might be random, class sizes might be small, or teacher turnover could be high in Atlanta.

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution also examined test results for 69,000 schools in 49 states and found “high concentrations of suspect scores” in 196 school districts. See these results, along with a more detailed methodology and a list of study consultants with their feedback here. The New Yorker has a detailed story about the people/logistics involved in cheating at an Atlanta middle school: "Wrong Answer", July 21, 2014.

Submitted by Margaret Cibes

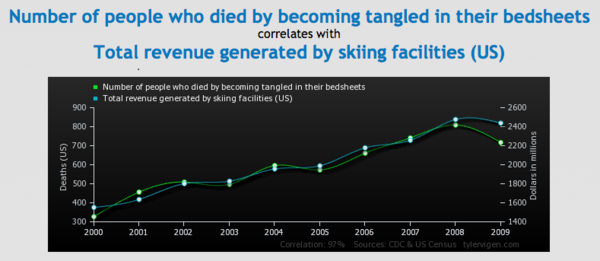

More spurious correlations

Chance News 99 observed that Tyler Vigan's amusing Spurious Correlations project had been referenced on the Rachel Maddow show. Margaret Cibes sent the post below, where we see that Business Insider has also picked up on this.

- “These Hilarious Charts Will Show You That Correlation Doesn’t Mean Causation”

- by Dina Spector, Business Insider, May 9, 2014

- The author provides some sample charts, all of which – and more - can be found at the website Spurious Correlations, by Tyler Vigan, who also provides raw data for each chart, although not always clear sources for the data. There is also a short video by Vigan.

- Here’s one that shows the number of people who died by becoming entangled in their bedsheets versus the total revenue generated by skiing facilities, where r = +0.969724:

The hot hand, revisited

Ethan Brown sent the following links to the Isolated Statisticians e-mail list:

- Does the 'hot hand' exist in basketball?, by Ben Cohen, Wall Street Journal, 27 February 2014

- The hot hand: A new approach to an old “fallacy”, by Andrew Bocskocsky, John Ezekowitz, and Carolyn Stein, MIT Sloan Spots Analytics Conference, 28 February-1 March, 2014

The WSJ story is reporting on a new study presented at the MIT conference. The researchers found a "small yet significant hot-hand effect" after examining a data set consisting of some 83,000 shots from last year's NBA games. The analysis was facilitated by the extensive video records now available. In contrast to earlier studies, their model took into account the potential increase of difficulty of successive shots in a streak. For example, "hot" players might attempt longer shots, or draw tighter coverage from defenders. Conditioning on the difficulty of the current shot, the researchers found a 1.4 to 2.8 percentage point improvement in success rate after several previous shots had been made.

Discussion

1. On practical vs. statistical significance: How important would such an effect be in a game? Can you think of a way to measure it?

2. It certainly sounds plausible, as suggested in the paper, that a player who feels "hot" might attempt more difficult shots and/or draw more defenders. Do you think the many fans who believe in the hot hand take such things into account? That is, would a player whose shot percentage was constant, but whose shot difficulty was increasing, be popularly regarded as "hot"? What about a player, who, facing increased defensive pressure, passed to teammates receiving less focus from defenders?

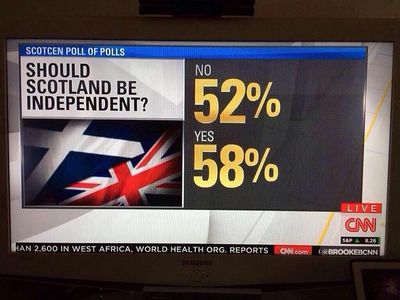

Scotland's independence referendum

There has been a lot of news surrounding the Scottish referendum. Paul Alper sent this

Scotland’s ‘No’ vote: A loss for pollsters and a win for betting markets

by Justin Wolfers, "The Upshot" blog, New York Times, 19 September 2014

Wolfers reports on how badly the pollsters did on Scotland's referendum: pollsters predicted a very close result but was in the end there was actually a ten point difference. He writes, "Typically, asking people who they think will win yields better forecasts, possibly because it leads them to also reflect on the opinions of those around them, and perhaps also because it may yield more honest answers. ...Indeed, in giving their expectations, some respondents may even reflect on whether or not they believe recent polling."

Margaret Cibes also sent links to this and also a pre-election piece by the same author:

Betting markets not budging over poll on Scottish independence

by Justin Wolfers, "The Upshot" blog, New York Times, 8 September 2014

At that time, a new opinion poll had just predicted a win for the independence movement, a result which upset British financial markets. Wolfers wrote:

The fast-moving news cycle may further shift public opinion — whether it’s recent promises for greater autonomy if the Scots remain within Britain or the announcement of another royal pregnancy. These broader uncertainties are never included in the so-called “margin of error” that comes with these polls.

But political prediction markets, in which people bet on the likely outcome, are all about evaluating and quantifying the full range of risks. And currently, bettors aren’t buying into the pro-independence hype.

Indeed, the betting markets showed much less volatility than the opinion polls, and in the end had it right.

in The Scotland independence polls were pretty bad (FiveThiryEight, 19 September 2014), Nate Silver had some musings about what went wrong with the polls. We know that in voluntary response polls, strong (and especially negative) opinions tend to be overrepresented. In addition, Silver suggests that less passionate voters--even when actually contacted by pollsters--might have been less willing to state a preference. Both these factors would understate the support for remaining in the UK. But since the turnout rate for the referendum was very high, this support ultimately counted.