Chance News 98

Quotations

"In statistics it's enough for our results to be cool. In psychology they're supposed to be correct. In economics they're supposed to be correct and consistent with your ideology."

Some other selections:

- “God created the world in 7 days and we haven’t seen much of him since.” (God draws θ from an urn and then is out of the picture)

- “People don’t go around introducing you to their ex-wives.” (why model improvement doesn’t make it into papers)

Submitted by Paul Alper

"In our lust for measurement, we frequently measure that which we can rather than that which we wish to measure...and forget that there is a difference."

“Statistics and Experimentation”, AP Statistics Reading, June 16, 2011

"'We value what we measure rather than measuring what we value' is an expression commonly heard in education circles these days."

Submitted by Margaret Cibes

From What the Numbers Say, by Niederman and Boyum, 2003:

“Unfortunately, Americans seem much better at producing numbers than making sense of them.” [p. 1]

“Distrusting numbers is not the same as disregarding them.” [p. 11]

“[G]ive more credence to a finding if there is good reason to believe it for reasons other than its statistical significance.” [p. 219]

“Elizabeth Taylor’s Law (the marital version of Pareto’s Law) reminds us that a small fraction of the population accounts for a disproportionate share of divorces.” [p. 17]

“[M]ost people not only lack a notation for dealing with small numbers, they also lack a vocabulary. If you show a man the number 3,500,000 and ask what it is, he will say, with little if any hesitation, ‘three and a half million’ … or ‘three million five hundred thousand.’ But if you show him 0.00000029, he will probably respond, ‘point oh oh oh oh oh oh two nine,’ slowly …. [J]ust imagine a politician describing the defense budget as ‘three six nine oh oh oh oh oh oh oh oh oh dollars.” [pp. 117-118]

Submitted by Margaret Cibes

Forsooth

A Google search for “apophenia” yielded the following:

(a) “the experience of seeing patterns or connections in random or meaningless data.”

(b) “an example of a Type I error … – the identification of false patterns in data.”

(c) “heavily documented as a source of rationale behind gambling, with gamblers imagining they see patterns in the occurrence of numbers in lotteries, roulette wheels, and even cards.”

(d) “an open statistical library for working with data sets and statistical models. It provides functions on the same level as those of the typical stats package … but gives the user more flexibility to be creative in model-building.” [emphasis added]

Submitted by Margaret Cibes

From What the Numbers Say, by Niederman and Boyum, 2003:

“Out there, just in our galaxy alone, there are 400 billion stars. If only one out of a million of those had planets, and if just one of a million of those had life, and if just one out of a million of those had intelligent life, there would be literally millions of civilizations out there.” [citing film Contact, pp. 105-106]

“Ninety-nine times out of 10 you’re not going to win like that.” [citing USAF Academy football coach Fisher DeBerry, p. 172]

“In 1998 there were 361 fatal accidents out of 39 million flights. The ‘risk’ of a fatal accident is only 0.000009 percent.” [citing letter defending airline safety, p. 172]

Submitted by Margaret Cibes

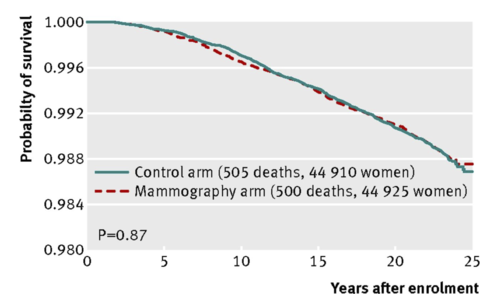

Some frightening graphs

Most people believe that

- Unless treated, cancer is necessarily fatal; and

- The earlier cancer is diagnosed and treated, the more likely the cure

Because cancer is a catchall term, #1 is certainly wrong. Some cancers grow so slowly that death is due to another cause. Indeed, some cancers are so indolent that a person may lead an entire life unaware even of the existence of the cancer. Therefore, in spite of its plausibility, #2 is suspect because diagnoses based on a screening test might lead to unnecessary and harmful treatments.

The following five graphs found in an article by Welch and Black illustrate this conundrum of modern medicine: it can do a great deal of harm precisely because it is so good at doing things such as finding abnormalities which represent non-threatening deviations from what is deemed normal.

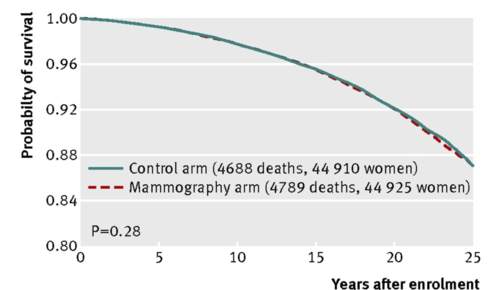

Notice that for each of the five cancers, its time series of mortality is flat whereas the number of new diagnoses rises prohibitively over time indicating overdiagnosis and therefore, overtreatment with consequent suffering. As another instance of overdiagnosis, overtreatment and consequent suffering, the following three figures are taken from an article by Miller, et al, in the British Medical Journal (BMJ 2014;348:g366 doi: 10.1136/bmj.g366), entitled “Twenty five year follow-up for breast cancer incidence and mortality of the Canadian National Breast Screening Study: randomised screening trial.”

- Fig 2 All cause mortality, by assignment to mammography or control arms (all participants)

- Fig 3 Breast cancer specific mortality, by assignment to mammography or control arms (all participants)

- Fig 4 Breast cancer specific mortality from cancers diagnosed in screening period, by assignment to mammography or control arms

This very large--a sample size of approximately 90,000-- 25 year randomized control trial concludes that

Annual mammography in women aged 40-59 does not reduce mortality from breast cancer beyond that of physical examination or usual care when adjuvant therapy for breast cancer is freely available. Overall, 22% (106/484) of screen detected invasive breast cancers were over-diagnosed, representing one over-diagnosed breast cancer for every 424 women who received mammography screening in the trial.

Discussion

1. With regard to the five time series, suppose instead of overdiagnosis and overtreatment, the following (reverse causality) argument is made: despite the rise in each of the cancers, modern medicine has kept the mortality constant. Comment on this assertion.

2. Notice that in the above Figs 2, 3 and 4, a p-value is given for the comparison between the mammography arm and the control arm. Looking at the curves themselves, comment as to why it makes sense that each of the p-values is well above the mystical .05.

3. With regard to the mammography study, there is an accompanying editorial in the BMJ entitled “Too much mammography.” This editorial goes on to compare and contrast PSA screening with mammography. Although PSA screening and mammography seem to be very similar "owing to [the] small effect on mortality and large risk of overdiagnosis ([1]),"

Nevertheless, the UK National Screening Committee does recommend mammography screening for breast cancer but not prostate specific antigen screening for prostate cancer.

Because the scientific rationale to recommend screening or not does not differ noticeably between breast and prostate cancer, political pressure and beliefs might have a role.

We agree with Miller and colleagues that “the rationale for screening by mammography be urgently reassessed by policy makers.” As time goes by we do indeed need more efficient mechanisms to reconsider priorities and recommendations for mammography screening and other medical interventions. This is not an easy task, because governments, research funders, scientists, and medical practitioners may have vested interests in continuing activities that are well established.

Comment on the vested interests and why the task is difficult.

4. Although the study by Miller is in some sense a bombshell, note that evidence has existed for over 10 years previous that mammography screening for women under 60 years of age had severe problems.

Our finding of increased mastectomies has consistently been ignored by screening advocates for 10 years, and information from many cancer charities and governmental agencies continues to state the opposite – that screening decreases mastectomies - despite having no reliable data to support this claim.

As another instance of a (personal) vested interest, and to show how difficult it is to discuss the problems of mammography screening as seen by evidence based medicine, diplomatically engage a female and bring up the topic.

5. This is a link to a presentation given by Dr. H. Gilbert Welch a few years ago and thus, does not include the Miller Canadian study mentioned above. The video is 99 minutes in length but well worth seeing in its entirety. He discusses the five time series at length and he illustrates the deficiencies of mammography as was known then.

Submitted by Paul Alper