Chance News 111

Under contruction: July 1, 2017 to ...

Quotations

“In my darkest moods I follow what could be called the ‘Groucho principle’: because stories have gone through so many filters that encourage distortion and selection, the very fact that I am hearing a claim based on statistics is reason to disbelieve it.”

'Exaggerations' threaten public trust in science, says leading statistician, Guardian, 28 June 2017

"Aside from ruining the rest of the 21st century, the 2016 U.S. election inflicted spectacular collateral damage on the subject known as statistics."

Forsooth

COLONEL [Buzz] ALDRIN: Infinity and beyond. (Laughter.)

THE PRESIDENT: This is infinity here. It could be infinity. We don’t really don’t know. But it could be. It has to be something -- but it could be infinity, right?

Okay. (Applause.)

Office of the White House Press Secretary, 30 June 2017.

Suggested by Mike Olinick

Do we have to?

Photo by Pete Schumer, taken in the elevator at his hotel.

"Random" seat assignment

Ryanair's 'random' seat allocation not random — scientists

by John von Radowitz, Irish Independent, 30 June 2017

Ryanair is an Irish low-cost airline. This Wikipedia entry reports that they have repeatedly faced criticism for misleading advertising.

The Irish Independent article concerns a recent controversy. When customers book Ryanair flights, they can pay to make a seat selection or else opt for "random" seat assignment, which is free. Advertising on the airline's website says, "Can't stand the middle seat? Don't leave it to chance, take your pick from a choice of seats. Get up to 50pc off reserved seats with prices starting at £2."

But is it up to chance? In light of customer complaints, the BBC consumer affairs show Watchdog sought expert opinion from Oxford University. To test the claim, researchers had four groups of four passengers book travel on four separate flights, all under the random seating option. On every flight, all of the passengers got middle seats. The odds of this happening were estimated at about 1:540,000,000, much longer than the 1:45,000,000 odds of winning the UK National Lottery jackpot. The director of Oxford University's Statistical Consultancy, Dr. Jennifer Rogers, is quoted as saying, "This is a highly controversial topic and my analysis cast doubt on whether Ryanair's seat allocation can be purely random."

The article concludes with the following explanation from Ryanair, which qualifies as an extended Forsooth!

We haven't changed the random seat allocation policy.

The reason for more middle seats being allocated is that more and more passengers are taking our reserved seats (from just £2) and these passengers overwhelmingly prefer aisle and window seats which is why people who choose random (free of charge) seats are more likely to be allocated middle seats.

Some random seat passengers are confused by the appearance of empty seats beside them when they check-in up to four days prior to departure.

The reason they can't have these window or aisle seats is that these are more likely to be selected by reserved seat passengers, many of whom only check in 24 hours prior to departure.

Since our current load factor is 95pc, we have to keep these window and aisle seats free to facilitate those customers who are willing to pay (from £2) for them.

Submitted by Patrick O'Beirne

Sense and Sensibility and Statistics

From The Word Choices That Explain Why Jane Austen Endures

by Kathleen A. Flynn and Josh Katz, New York Times, 6 July 6, 2017.

Jane Austen' popularity has endured, and there may be something in her language that explains this. A principal components analysis of the words used by a large number books published from 1701 t0 1920 show that Austen's novels were unusual in her use of words related to time (always, fortnight and week) or emotion (awkward, decided, dislike, glad, sorry, suppose).

Jane Austen also uses a large number of intensifying words: quite, really, and very. These words are normally avoided by authors, but Austen uses them to develop a sense of irony. This fits in well with some non-statistical assessments.

Traditional literary approaches to Austen have long focused on this aspect of her work: “the incongruities between pretence and essence, between the large idea and the inadequate ego," as the critic Marvin Mudrick put it. A look at passages where words like very are used frequently often finds the stated meaning conceivably at odds with the real one, the exaggeration subtly inviting doubt."

A nice interactive plot shows the first two principal components and you can hover over individual data points to see the book title.

Submitted by Steve Simon

Gerrymandering

Partisan gerrymandering has benefited the GOP, analysis shows

NBCnews.com, 25 June 2017

Republican electoral gains in 2010 gave the party substantial control over the redistricting that followed the 2010 Census. NBC reports on a statistical analysis by the Associated Press showing the effect in subsequent elections and the state and national levels. For example, in the 2016 election, they estimate that Republicans won approximately 22 more seats in the US House of Representatives than they would have been obtained if representation was proportional to vote share. The AP website reports that Texas had the largest gain, nearly 4 extra seats.

Gerrymandering is of course nothing new. The reference to Texas brought to mind a famous story, retold in a 2002 story from the Economist (How to rig an election, 25 April 2002): "[It] used to be said of the old Texas 6th (which was a road from Houston to Dallas), that you could kill most of the constituents by driving down the road with the car doors open."

However, the latest efforts are seen as particularly egregious. We read,

The AP’s analysis was based on an “efficiency gap” formula developed by University of Chicago law professor Nick Stephanopoulos and Eric McGhee, a researcher at the nonpartisan Public Policy Institute of California. Their mathematical model was cited last fall as “corroborative evidence” by a federal appeals court panel that struck down Wisconsin’s Assembly districts as an intentional partisan gerrymander in violation of Democratic voters’ rights to representation. The U.S. Supreme Court has agreed to hear an appeal.

Stephanopoulos and McGhee computed efficiency gaps for four decades of congressional and state House races starting in 1972, concluding the pro-Republican maps enacted after the 2010 Census resulted in “the most extreme gerrymanders in modern history.”

Here is how Stephanopoulos explained the efficiency gap idea in a 2014 article, Here's how we can end gerrymandering once and for all (New Republic, 2 July 2014):

The efficiency gap is simply the difference between the parties’ respective wasted votes in an election, divided by the total number of votes cast. Wasted votes are ballots that don’t contribute to victory for candidates, and they come in two forms: lost votes cast for candidates who are defeated, and surplus votes cast for winning candidates but in excess of what they needed to prevail. When a party gerrymanders a state, it tries to maximize the wasted votes for the opposing party while minimizing its own, thus producing a large efficiency gap. In a state with perfect partisan symmetry, both parties would have the same number of wasted votes.

NBC news also cites another analysis approach, introduced by the Princeton University Gerrymandering Project, launched this year by Sam Wang. In the inaugural post we read that, according to their analysis, "the extreme Republican advantages in some states were no fluke. The Republican edge in Michigan's state House districts had only a 1-in-16,000 probability of occurring by chance; in Wisconsin's Assembly districts, there was a mere 1-in-60,000 likelihood of it happening randomly."

The FAQ on the Princeton Project site has a description of how the tests work.

Discussion

The figures quoted in the next to last paragraph are not "the probability of [the resulting advantage] occurring by chance." Why? How would you rewrite the statement?

Submitted by Bill Peterson

More on mortality

Further criticism of social scientists and journalists jumping to conclusions based on mortality trends

by Andrew Gelman, "Statistical Modeling, Causal Inference, and Social Science" blog, 11 July 2017

In Deaths of despair from the last installment of Chance News, we described the Angus-Deaton work on middle-age mortality, including commentary by Gelman and others. In this latest post, Gelman includes links to some other articles suggested by his readers.

Gelman reiterates his support for the project, which he believe has raised important issues. But he notesthat the omission age-adjustment was strange, since "reporting trends in mortality rates without age adjusting is like reporting trends in nominal prices without adjusting for the consumer price index."

Gelman and collaborators have produced a wealth of graphics related to the story, which are packaged in another post, Easier-to-download graphs of age-adjusted mortality trends by sex, ethnicity, and age group.

Greece prosecutes former chief statistician

Greece’s troubling prosecution of its former chief statistician: Why Congress and State should speak up

by Barry D. Nussbaum and Katherine K. Wallman, Huffington Post, 7 July 2017

The authors of this op-ed are present and past presidents of the American Statistical Association. They describe how Andreas Georgiou, the former chief statistician of Greece, is being prosecuted for his reporting on the Greek national debt. The issue is not his work, which has actually produced a more accurate accounting, but rather the revelation that the debt is larger than previously understood, which will require stricter austerity measures. Nussbaum and Wallman call for US government officials to stress the need for transparent statistical data, and more generally to condemn attacks on science.

In the US, statisticians are not being prosecuted for their analyses. However, the Greek saga calls to mind how climate scientists have been subjected to harrassment. Indeed, in February Representative Lamar Smith (R-Texas), chair of House Science Committee, convened hearings dubiously titled “Making EPA Great Again”.

In another recent story, the director of the US Census Bureau John Thompson announced his resignation this May. In an interview with NPR, Could a census without a leader spell trouble In 2020? (NPR "Code Switch", 15 July 2017), Thompson expressed confidence that work at the bureau would continue its work without disruption. Some observers have expressed concern because the 2020 census is fast approaching. Allocation of funds for many federal programs is dependent on census data. The counts are also have implications for Congressional redistricting. The Trump adminstration has so far been slow at filling top jobs.

Submitted by Bill Peterson

Still running against Hillary?

Paul Alper sent a link to the following article.

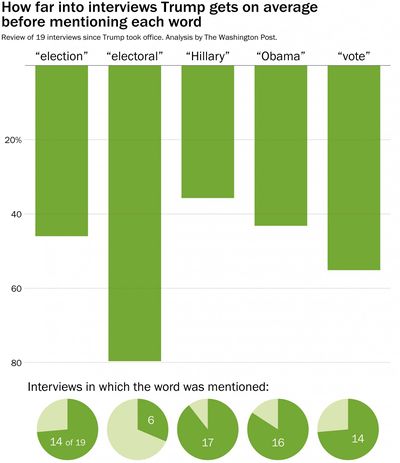

- Trump can usually make it about a third of the way through an interview without mentioning Hillary Clinton

- by Philip Bump, Washington Post, 21 July 2017

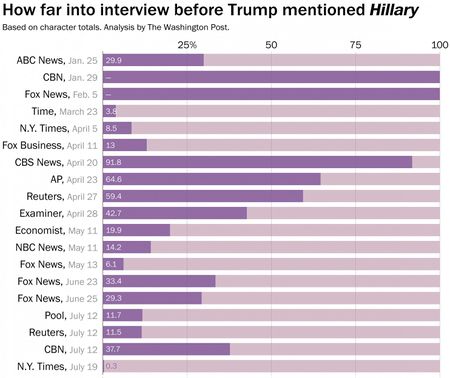

Political observers have noted that President Trump thrives on campaign-style events, and that his communications regularly lapse into campaign rhetoric. The Post presents a quantitative analysis of how often Trump invokes the name of his 2016 opponent, Hillary Clinton, and other terms relating to the election. The following graphic from the article shows, for the 19 interviews Trump has given, which them have included such references, and how far into the interview the reference first appears.

Hillary Clinton's name is the "winner", coming up in 17 interviews, appearing on average less than 40% of the way through!

Moreover, the Post found that the two interviews without Hillary references (coded as appearing 100% of the way through) came early in his term, whereas she was mentioned almost immediately in his recent July 19 interview with the New York Times.

Similar graphs are constructed for the other terms. Links to the interviews themselves are provided at the end of the article. Quoting the beginning of the transcript of that last interview from the Times:

TRUMP: Hi fellas, how you doing?

BAKER: Good. Good. How was your lunch [with Republican senators]?

TRUMP: It was good. We are very close. It’s a tough — you know, health care. Look, Hillary Clinton worked eight years in the White House with her husband as president and having majorities and couldn’t get it done. Smart people, tough people — couldn’t get it done. Obama worked so hard... (emphasis added)

As the Post reported, he got though just 20 words before "Hillary." The caption for the second graphic says that the figures are based on "character analysis." This is not explicitly defined in the article, but the preceding suggests that it means counting words spoken by Trump and computing the words spoken before the first "Hillary" divided by his total words spoken.

Discussion

- From the first graphic, it appears that the terms that came up in many interviews also tended to come up early. Is this surprising? Can you think of another way to reveal this information?

- From the second graphic, consider distribution for the point at which "Hillary" first occurs. Does this square with headline? What is happening here?

Voter fraud and the birthday problem

This anti-voter-fraud program gets it wrong over 99 percent of the time. The GOP wants to take it nationwide.

by Christopher Ingraham, Washington Post 'Wonkblog', 20 July 2017

Throughout the 2016 campaign, candidate Trump warned that the election was being rigged. After the election, he complained that Hillary Clinton would not have won the popular vote without millions of illegal ballots. Such claims have cast a shadow over the recently convened Presidential Advisory Commission on Election Integrity, despite Vice President Pence's assurances that "this commission has no preconceived notions."

Kansas Secretary of State Kris Kobach is the vice-chairman of the commission. As described in the Post, he has advocated national implementation of Kansas program called Interstate Voter Registration Crosscheck, which seeks to identify people who may be voting in more than one location. Other states are invited to send their voter registration lists to Kansas, and Crosscheck will search for voters with matching first name, last name and date of birth. The idea is to remove duplicate registrations, though it is not exactly clear how this would be implemented.

Critics of the program argue that it creates many "false positives"; that is, different people with matching names and birthdays. From the article we read:

A statistical analysis of the program (One person, one vote: estimating the prevalence of double voting in U.S. presidential elections ) published earlier this year by researchers at Stanford, Harvard, University of Pennsylvania and Microsoft, for instance, found that Crosscheck “would eliminate about 200 registrations used to cast legitimate votes for every one registration used to cast a double vote.”

Ostensibly, Crosscheck appears to assume that a match on name and birthdate indicates a duplicate registration by the same person. Calculating the chance of such a match among different people is an application of a famous problem from probability. The Post cites a 2007 paper, Seeing double voting: An extension of the birthday problem. It is well-known that among 23 randomly selected birthdays (month and day), there is a better than even chance that at least two will match. With 180 people, the article reports that there is a 50% chance that two will match birthdates (month, day and year). There is a built-in function in R called qbirthday that implements such calculations. For example:

> qbirthday(prob=0.5, classes=365, coincident=2)

[1] 23

> qbirthday(prob=0.5, classes=365*65, coincident=2)

[1] 182

For the second calculation we assume that an individual has 65 years of voting eligibility. (It is also assumed in both calculations that all birthdays are equally likely. But if they are not, then coincidences are even more likely ). For common names, this is a very real problem. For instance, the article reports that 282 William Smiths were registered in New Jersey in 2004. As an example of how such coincidences can accumulate, the "One person, one vote" paper found that In 2012 and 2014, the Crosscheck program found nearly 240,000 voter registrations in Iowa that matched the name and birthdate of a record in some other state.

Beyond these probabilistic worries are the mechanics of integrating records across states and municipalities, with the challenges of missing data fields, transcription errors, and the like.

Submitted by Bill Peterson