Chance News 91: Difference between revisions

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

Submitted by Paul Alper | Submitted by Paul Alper | ||

---- | |||

“If you want to eat sausage and survive, you should know what goes on in the factory. That dictum … most definitely applies to the statistical sausage factory where medical data is ground into advice.” | |||

<div align=right>Review of <i>Naked Statistics</i>, by Dartmouth economist Charles Wheelan<br> | |||

[http://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/29/science/naked-statistics-by-charles-wheelan-review.html?_r=0 “A Crash Course in Playing the Numbers”]<br> | |||

<i>The New York Times</i>, January 28, 2013</div> | |||

Submitted by Margaret Cibes at suggestion of James Greenwood | |||

==Forsooth== | ==Forsooth== | ||

Revision as of 13:40, 31 January 2013

Quotations

"As I wrote a couple years ago, the problem, I think, is that they (like many economists) think of statistical methods not as a tool for learning but as a tool for rigor. So they gravitate toward math-heavy methods based on testing, asymptotics, and abstract theories, rather than toward complex modeling. The result is a disconnect between statistical methods and applied goals.

"For the psychologists you’re looking at, the problem is somewhat different: they do want to use statistics to learn, they’re just willing to learn things that aren’t true."

Submitted by Paul Alper

"Hendry’s standing at the back window with a shotgun, scanning for priors coming over the hill, while a million assumptions just walk right into his house through the front door."

Submitted by Paul Alper

“If you want to eat sausage and survive, you should know what goes on in the factory. That dictum … most definitely applies to the statistical sausage factory where medical data is ground into advice.”

The New York Times, January 28, 2013

Submitted by Margaret Cibes at suggestion of James Greenwood

Forsooth

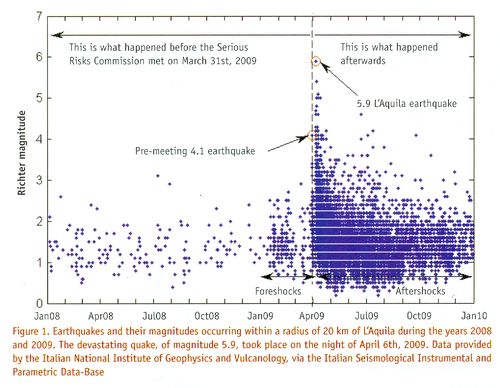

Aquila earthquake chart

“The L’Aquila earthquake: Science or risk on trial”

by Jordi Prats, Significance magazine, December 2012

Prats discusses the April 2009 Italian earthquake during which about 300 residents lost their lives. Readers will recall news about the 13-month trial of the six scientists (and a government official), who were each sentenced to six years in prison for “providing ‘inaccurate, incomplete and contradictory information’ on the probability and risk of an earthquake and for falsely reassuring the population.” (See “The perils of failed predictions”, Chance News 89, October-November 2012.)

Prats reports that, according to the Italian Macroseismic Database, "L’Aquila has suffered earthquakes of magnitude 6 or higher on 13 occasions in the period 1315-2005, approximately every 50 years." Also, he reports that, according to a 1988 seismology paper, “Alarm systems based on a pair of short-term earthquake precursors”, "[T]he probability of a weak shock or swarm being followed by a major shock in the following 2-5 days is very low, of the order of 1-5%."

Prats believes that the most important information for the public would have been the risk (in the sense of expected loss) of an earthquake, and not the just its likelihood, because such a risk assessment would have included both the probability of an earthquake and the expected loss in the event of an earthquake.

In any case, Significance Editor Julian Chamkin has given permission to post the following chart from the article (email of January 14, 2013):

Discussion

1. Based on the chart, would you have recommended that the Aquila public be informed, in March or April of 2009, that they should be prepared for a serious earthquake? (Note that, according to Wikipedia[1], someone who made a March 2009 prediction of a major earthquake was accused of being "alarmist," and “forced to remove his findings from the Internet.”)

2. Consider the Challenger spacecraft disaster in 1986. The O-ring chart made famous by Edward Tufte[2] suggested potential problems with launching a spacecraft at the near-freezing temperature at which it was actually launched. An online article, “Representation and Misrepresentation: Tufte and the Morton Thiokol Engineers on the Challenger”, discusses the role of the engineers in that decision, with respect to the information available to them and to their professional ethical responsibilities. Interested readers may also check out a Berkeley professor's Q&A activity sheet, “Challenger O-Ring Data Analysis”, about the Challenger O-ring issue.

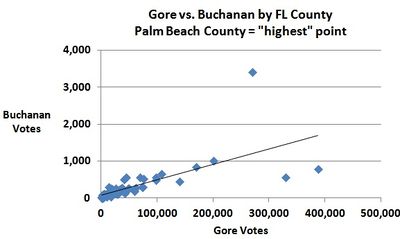

3. While we're on the topic of decision-making based, at least partially, on charts, see the chart below, which shows U.S. presidential election results in Florida for a major-party (Gore) and minor-party (Buchanan) candidate. Based on the chart, what might you have recommended to an election official? See "Why Usability Testing Matters".

Submitted by Margaret Cibes

Re #3, Bill Peterson called attention to the article, "Voting Irregularities in Palm Beach, Florida", Chance magazine, 2001, which contains a similar chart comparing Buchanan's votes in the 1996 primary to those in the 2000 election.

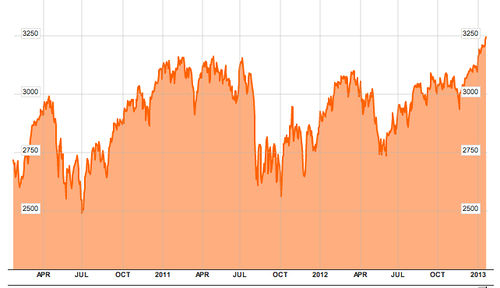

A(nother) Random Walk Down Wall Street

“Investments: Orlando is the cat's whiskers of stock picking”

by Mark King, The Observer, January 12, 2013

During the forty years between the first publication of Burton Malkiel's A Random Walk Down Wall Street (in 1973) through its most recent (10th) edition (in 2011) there have been numerous attempts to test Malkiel's contention that "a blindfolded chimpanzee throwing darts at the stock listings can select a portfolio that performs as well as those managed by the experts." (Not surprisingly, Chance News has also been following many of these efforts-- see below.)

The set-up here is typical: a panel of financial experts is pitted against a "random" process to choose, buy, and sell stocks, which in the current version is achieved through the antics of a cat named Orlando. "While the professionals used their decades of investment knowledge and traditional stock-picking methods", the article says, "the cat selected stocks by throwing his favourite toy mouse on a grid of numbers allocated to different companies." For an additional comparison, a third process of investing was included-- by a group of high school students. The Observer designed and oversaw the "portfolio challenge", as they called it, which was a year-long effort ending on December 31, 2012:

Each team invested a notional £5,000 in five companies from the FTSE All-Share index at the start of the year. After every three months, they could exchange any stocks, replacing them with others from the index. By the end of September the professionals had generated £497 of profit compared with £292 managed by Orlando. But an unexpected turnaround in the final quarter has resulted in the cat's portfolio increasing by an average of 4.2% to end the year at £5,542.60, compared with the professionals' £5,176.60.

The students fared the worst, ending down £160 for the year.

The chart below shows the 3-year activity of the FTSE All-Share index (from Bloomberg Market Data):

The starting and ending values for last year (12/30/11 to 12/31/12) are 2857.88 and 3093.41, yielding an 8.24% increase for the index. During the same period, Orlando's method produced a 10.84% increase, while the experts gained 3.52%.

Discussion

1. The details of Orlando's protocol are not provided in the article. Does it appear to be a random process? Why or why not? If not, can you devise a random process for Orlando to use?

2. The high school students who took part in the project attend the John Warner School (in Hertfordshire, England.) The school's deputy headteacher, Nigel Cook, is quoted: "The mistakes we made earlier in the year were based on selecting companies in risky areas. But while our final position was disappointing, we are happy with our progress in terms of the ground we gained at the end and how our stock-picking skills have improved."

Do you think the phrase our stock-picking skills have improved is warranted? Why or why not?

Submitted by Jeanne Albert

Fecal matter matters

When pills fail, this, er, option provides a cure

by Denise Grady, New York Times, 17 January 2013

In case you never worried about Clostridium difficile bacteria, the article points out that the disease caused by C. difficile bacteria “kills 14,000 people a year in the United States.” We read that “this stubborn and debilitating infection.. is usually caused by antibiotics, which can predispose people to C. difficile by killing normal gut bacteria. If patients are then exposed to C. difficile, which is common in many hospitals, it can take hold.”

The usual treatment involves more antibiotics, but about 20 percent of patients relapse, and many of them suffer repeated attacks, with severe diarrhea, vomiting and fever.

Hence, the use of fecal transplants from a healthy person into the gut of the one who is ill in order to reestablish a healthy gut:

Researchers say that, worldwide, about 500 people with the infection have had fecal transplantation. It involves diluting stool with a liquid, like salt water, and then pumping it into the intestinal tract via an enema, a colonoscope or a tube run through the nose into the stomach or small intestine.

Although reported success rates of fecal transplants have been high, evidenced based medicine requires a randomized controlled trial. This can be found at the January 17, 2013 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine.

We randomly assigned patients to receive one of three therapies: an initial vancomycin regimen (500 mg orally four times per day for 4 days), followed by bowel lavage and subsequent infusion of a solution of donor feces through a nasoduodenal tube; a standard vancomycin regimen (500 mg orally four times per day for 14 days); or a standard vancomycin regimen with bowel lavage. The primary end point was the resolution of diarrhea associated with C. difficile infection without relapse after 10 weeks.

The study was stopped after an interim analysis. Of 16 patients in the infusion group, 13 (81%) had resolution of C. difficile–associated diarrhea after the first infusion. The 3 remaining patients received a second infusion with feces from a different donor, with resolution in 2 patients. Resolution of C. difficile infection occurred in 4 of 13 patients (31%) receiving vancomycin alone and in 3 of 13 patients (23%) receiving vancomycin with bowel lavage (P<0.001 for both comparisons with the infusion group). No significant differences in adverse events among the three study groups were observed except for mild diarrhea and abdominal cramping in the infusion group on the infusion day. After donor-feces infusion, patients showed increased fecal bacterial diversity, similar to that in healthy donors, with an increase in Bacteroidetes species and clostridium clusters IV and XIVa and a decrease in Proteobacteria species.

Discussion

1. The infusion group had 13 successes out of 16. The combined non-infusion group had 7 successes out of 26. Use whatever statistics package you fancy and carry out a t-test and CI for two proportions to show that the treatment is statistically significant.

2. Clearly, the medical world, at least as seen through the eyes of journalists, implicitly believes that this infusion treatment is clinically (i.e., practically) significant. However, after reading the two articles mentioned and any of the many others about the New England Journal of Medicine study found via Google, what ingredients are missing when it comes to clinical significance?

3. This randomized clinical trial is referred to as an open-label clinical trial. What does that mean and why was that necessary?

4. According to the original journal article, “The study was stopped after an interim analysis.” What conditions (good and bad) would lead to a randomized clinical trial being stopped?

5. No discussion of the usefulness of transplanting fecal material would be complete without mentioning "Coprophagia" and koala bears. Go to here to see how common coprophagia is among diverse species.

Submitted by Paul Alper

More on Nate Silver's new book

See this discussion in Chance News 90 of Nate Silver's The Signal and the Noise.

Following up on this post, Paul Alper sent links to two more reviews from Andrew Gelman's blog. Paul also noted the spirited Bayesian vs. frequentist exchange in the comments there. In that vein, he sent the following cartoon

which has appeared in various places on the web (see here and here).

Historic atlases available for chart junkies

“The Motley Roots of Data Visualization in 19th Century Census Charts”

by Jeffrey Rotter, the Atlantic CITIES, January 28, 2013

While looking for ways to visualize old U.S. census data, Jonathan Soma, a self-styled stats junkie, “discovered a trove of maps and charts in a musty backroom of the Library of Congress web site.” These were three Statistical Atlases of the U.S.A. (1870, 1880, 1890).

Soma has compiled the three atlases (384 pages), into A Handsome Atlas and organized the pages into eight topics and eight visualizations. The reviewer writes:

And they are wonders to behold, with or without the numbers.

(For other, albeit non-atlas, charts, see “Choices in statistical graphics: My stories”, for Andrew Gelman's slides from a talk he gave at the New York Data Visualization Meetup on January 14, 2013.)

Submitted by Margaret Cibes