Sandbox: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

== | ==Odds are, it's wrong== | ||

[http:// | [http://www.sciencenews.org/view/feature/id/57091/title/Odds_Are,_Its_Wrong Odds are, it's wrong]<br> | ||

by | by Tom Siegfried, ''Science News'', 27 March 2010 | ||

This is a provocative essay on the limitations of significance testing in scientific research. The main themes are that it is easy to do the such tests incorrectly, and, even when they are done correctly, they are subject to widespread misinterpretation. | |||

Submitted by Bill Peterson, based on a suggestion from Scott Pardee | |||

'''Discussion Questions''' | '''Discussion Questions''' | ||

1. | 1. (suggested by Bill Jefferys) Box 2, paragraph 1 of the article states "Actually, the P value gives the probability of observing a result if the null hypothesis is true, and there is no real effect of a treatment or difference between groups being tested. A P value of .05, for instance, means that there is only a 5 percent chance of getting the observed results if the null hypothesis is correct." Why is this statement wrong? | ||

==Tea party graphics== | ==Tea party graphics== | ||

Revision as of 00:55, 4 May 2010

Odds are, it's wrong

Odds are, it's wrong

by Tom Siegfried, Science News, 27 March 2010

This is a provocative essay on the limitations of significance testing in scientific research. The main themes are that it is easy to do the such tests incorrectly, and, even when they are done correctly, they are subject to widespread misinterpretation.

Submitted by Bill Peterson, based on a suggestion from Scott Pardee

Discussion Questions

1. (suggested by Bill Jefferys) Box 2, paragraph 1 of the article states "Actually, the P value gives the probability of observing a result if the null hypothesis is true, and there is no real effect of a treatment or difference between groups being tested. A P value of .05, for instance, means that there is only a 5 percent chance of getting the observed results if the null hypothesis is correct." Why is this statement wrong?

Tea party graphics

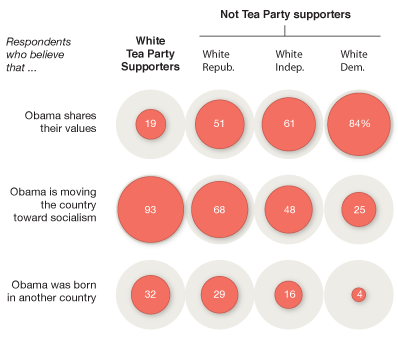

A mighty pale tea

by Charles M. Blow, New York Times, 16 April 2010

This article recounts Blow's experience visiting a Tea Party rally as a self-identified "infiltrator." He was interested in assessing the group's diversity. Reproduced below is a portion of a graphic, entitled The many shades of whites, that accompanied the article.

The data are from a recent NYT/CBS Poll.

Submitted by Paul Alper