Chance News 16: Difference between revisions

| Line 83: | Line 83: | ||

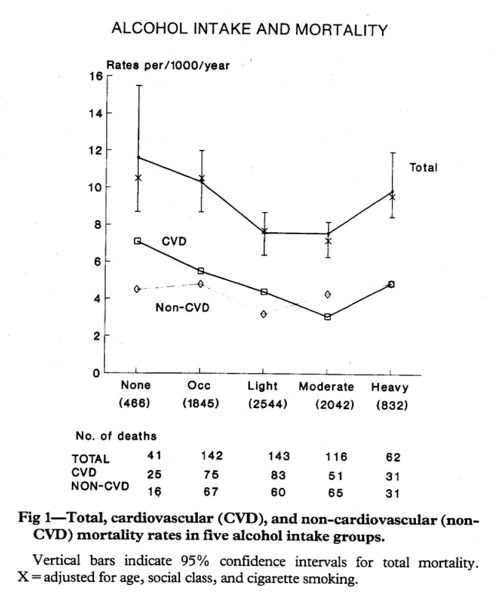

A large numbers of observational studies | A large numbers of observational studies have suggested that moderate drinkers have a lower risk for heart attacks than nondrinkers or heavy drinkers. The results of these studies are usually illustrated by a U shaped graphic like this: | ||

<center>[[Image:wine1.jpg|500px|]] | <center>[[Image:wine1.jpg|500px|]] | ||

</center> | </center> | ||

This graphic | This graphic is from the article "Alcohol and Mortality in British Men; Explaining the U-Shaped Curve", ''The Lancet'', December 3, 1988, A. Shaper, et al. | ||

In their summary the authors wrote: | |||

<blockquote>In a prospective study of 7735 middle-aged British men, 504 of whom died in a follow-up period of 7.5 years, there was a U-shaped relationship between alcohol intake and total mortality and an inverse relationship with cardiovascular mortality, even after adjustment for age, cigarette smoking, and social class. These mortality patterns were seen in all smoking categories (with ex-smoking non-drinkers having the highest mortality) and were observed in manual but not in non-manual workers. The alcohol-mortality relationships are produced by pre-existing disease and by the movement of men with such disease into non-drinking or occasional-drinking categories. The concept of a "protective” effect of drinking on mortality, ignoring the dynamic relationship between ill-health and drinking behavior, is likely to be ill founded.</blockquote?> | <blockquote>In a prospective study of 7735 middle-aged British men, 504 of whom died in a follow-up period of 7.5 years, there was a U-shaped relationship between alcohol intake and total mortality and an inverse relationship with cardiovascular mortality, even after adjustment for age, cigarette smoking, and social class. These mortality patterns were seen in all smoking categories (with ex-smoking non-drinkers having the highest mortality) and were observed in manual but not in non-manual workers. The alcohol-mortality relationships are produced by pre-existing disease and by the movement of men with such disease into non-drinking or occasional-drinking categories. The concept of a "protective” effect of drinking on mortality, ignoring the dynamic relationship between ill-health and drinking behavior, is likely to be ill founded.</blockquote?> | ||

The authors are concerned that this and other similar studies are seriously flawed because they include subjects who have recently quit | The authors are concerned that this and other similar studies are seriously flawed because they include subjects who have recently quit drinking and who are typically older people with medical problems who are told by their doctors to quit drinking. They suggest that this could explain why those who don't drink have a higher mortality rate than moderate drinkers. Evidently this concern was not persued until a recent study of Kaye Fillmore and her colleagues to appear om the mext issie of the journal ''Addiction Research and Theory.'' | ||

The ''Chronicle'' article described the new study as follows: | The ''Chronicle'' article described the new study as follows: | ||

| Line 102: | Line 102: | ||

All seven of those studies found no significant differences in the health of those who drank -- or previously drank -- and those who never touched the stuff. The remaining 47 studies represent the body of research that has led to a general scientific consensus that moderate drinking has a health benefit. </blockquote> | All seven of those studies found no significant differences in the health of those who drank -- or previously drank -- and those who never touched the stuff. The remaining 47 studies represent the body of research that has led to a general scientific consensus that moderate drinking has a health benefit. </blockquote> | ||

The article quotes Dr. Tim Naimi at the Centers for Disease Control as saying " | The Chronical article quotes Dr. Tim Naimi at the Centers for Disease Control as saying "The whole field of 'moderate drinking' studies is deeply flawed" and goes on to say: | ||

<blockquote> In a study published in May 2005 in the ''American Journal of Preventive Medicine'', Naimi and other CDC colleagues found that the comparatively higher risk of heart disease in abstainers could be explained by socioeconomic factors rather than lack of protection from alcohol consumption. Non-drinkers, for example, tended to be poorer than drinkers, had less access to health care, and had less healthy diets.</blockquote> | |||

Note that in the 1988 article, Shaper and his colleagues were also concerned about difference in drinking habits of different groups, in particular manual and non-manual workers. | |||

Naimi says "Anyone who suggests that people should begin drinking, or drink more frequently, to reduce the risk of heart disease is misguided". | Naimi says "Anyone who suggests that people should begin drinking, or drink more frequently, to reduce the risk of heart disease is misguided". | ||

===DISCUSSION=== | ===DISCUSSION=== | ||

Revision as of 12:48, 14 April 2006

Quotation

It is as useless to debate whether an actual sequence of coin tossing was governed by the laws of probability as "to debate the table manners of children with six arms."

Joe Doob

Chances are, Michael Kaplan and Ellen Kaplan

Here's more from Doob on this subject:

Then and later the most embarrassing probability class lecture was the first, in which I tried to give a satisfying account of what happens when one tosses a coin. (A famous statistician told me that he solves the difficulty by never mentioning the context.) One wants to talk about a limit of a frequency, but "limit" has no meaning unless an infinite sequence is involved, and an infinite sequence is not an empirical concept. I made vague and heavily hedged remarks such as that the ratio I would like to have limit l/2 "seems to tend to 1/2", that the coin tosser "would be very much surprised if the ratio is not nearly 1/2 after a large number of tosses", and so on.

The students never seemed to be bothered by my vagueness. For that matter professionals who write about the subject are usually also unbothered, perhaps because they never seem to be tossing real coins in a real world under the influence of Newton's laws, which somehow are not mentioned in the writing.

Statist. Sci. 12, no. 4 (1997), 301–311

Submitted by Laurie Snell

Forsooth

Add forsooth item here

Add source here

Exponential decay in Biblical ages

WHY did people live longer BEFORE Noah's Flood than they did after it? written by Arnold C. Mendez, Sr. and published at BibleStudy.org.

While looking on the web for good examples of the coefficient of determination, I came across a statistical analysis of the ages of Biblical patriachs. Apparently the author believes in a literal interpretation of the Bible and wants to answer skeptical comments about the unusual ages reported for some of the patriarchs in the Bible.

"One of the most intriguing facts in the Bible is the immense life spans of the patriarchs before and just after the flood. Adam lived 930 years, Methuselah the longest lived of the patriarchs lived 969 years. Noah lived 950 years."

Why is it that no one today lives so long?

"After the flood the earth was completely different than the earth before. There were widespread global differences. These would include changes in the climate, composition of the atmosphere, hydrologic cycle, geologic features, cosmic radiation reaching the earth, ozone concentration, ultra violet light, background radiation, genetics, diet, and a host of other subtle and/or profound chemical and physiological changes. These changes caused a rapid decline of the longevity of post flood humanity."

The statistical model comes in the analysis of the decline in ages after the flood. An exponential decay model produces the following equation y=487.78exp(-0.0907x) where x represents the generation number. After 20 generations, the ages settles down to a more modern figure of 70 years. The coefficient of determination is 0.889.

"This means that the decay rate of the patriarch's death after the flood was only 11% from being a perfect match."

You can view a graph of the data and the fitted line below, taken directly from the article.

http://www.biblestudy.org/basicart/longflod.gif

The author argues that the ages must be genuine since they fit an exponential curve so well and the writers of the time would not have the mathematical sophistication to fake an exponential decay curve.

Questions

1. Does a coefficient of determination of 89% sound impressive to you? What do you think about the author's comment that this is "only 11% from being a perfect match"?

2. What other models (linear or non-linear) would be worth considering for this data?

3. Is there an alternative explanation for this pattern of ages?

Submitted by Steve Simon

Is Jerry Falwell's debate team really number 1 in the nation?

Adapted from Who's Counting: Distrusting Atheists

The NY Times Magazine, Newsweek, and 60 Minutes are three of the media outlets devoting considerable attention to the "national champion" debate team from conservative fundamentalist Jerry Falwell's Liberty University. But does the team deserve this number one ranking or is it bogus, an artifact of the way the so-called overall category

As bloggers Jim Hanas, Ed Brayton and others have observed (and as is briefly and unobtrusively buried in the Times article itself), the ranking is based on the performance of the team in all tournaments, including novice and junior varsity contests.

The way rankings are determined in the "overall" category, winning at any of these second-tier tournaments adds to the team's point total. Liberty, which has a broad-based program, enters many of them and racks up many of its points by doing so.

The schools with the top individual teams, however, often don't have novice or JV teams and usually don't enter many of the lesser tournaments.

Even with such extensive, but light opposition, and the points resulting from it, the Liberty varsity team seldom reaches the semifinals and has yet to win a single varsity tournament.

In fact, in the varsity rankings Liberty is 20th, not first, and, when the quality of its opponents is taken into account, it ranks even lower than that.

As Hanas remarks, referring to Liberty as the No. 1 team and one of the nation's great collegiate debate programs is a bit "like calling the best Division III basketball team the NCAA champion."

Another analogy is to the brief 1992 presidential campaign of Iowa Sen. Tom Harkin. He was way behind in the primaries, but some of his staffers jokingly suggested that their man was leading. In winning Minnesota, Iowa and Montana, they argued that he had captured the largest land mass of any of the contenders.

Submitted by John A. Paulos

Does a glass of wine a day keep the doctor away?

UCSF points out flaw in studies tying alcohol to heart health

San Francisco Chronicle, March 30, 2006

Sabine Russell

Moderate alcohol use and reduced mortality risk: Systematic error in prospective studies, Kaye M. Fillmore et al, Addiction Research and Theory, March 30, 2006.

A large numbers of observational studies have suggested that moderate drinkers have a lower risk for heart attacks than nondrinkers or heavy drinkers. The results of these studies are usually illustrated by a U shaped graphic like this:

This graphic is from the article "Alcohol and Mortality in British Men; Explaining the U-Shaped Curve", The Lancet, December 3, 1988, A. Shaper, et al.

In their summary the authors wrote:

In a prospective study of 7735 middle-aged British men, 504 of whom died in a follow-up period of 7.5 years, there was a U-shaped relationship between alcohol intake and total mortality and an inverse relationship with cardiovascular mortality, even after adjustment for age, cigarette smoking, and social class. These mortality patterns were seen in all smoking categories (with ex-smoking non-drinkers having the highest mortality) and were observed in manual but not in non-manual workers. The alcohol-mortality relationships are produced by pre-existing disease and by the movement of men with such disease into non-drinking or occasional-drinking categories. The concept of a "protective” effect of drinking on mortality, ignoring the dynamic relationship between ill-health and drinking behavior, is likely to be ill founded.</blockquote?>

The authors are concerned that this and other similar studies are seriously flawed because they include subjects who have recently quit drinking and who are typically older people with medical problems who are told by their doctors to quit drinking. They suggest that this could explain why those who don't drink have a higher mortality rate than moderate drinkers. Evidently this concern was not persued until a recent study of Kaye Fillmore and her colleagues to appear om the mext issie of the journal Addiction Research and Theory.

The Chronicle article described the new study as follows:

Fillmore and colleagues from the University of Victoria, British Columbia; and Curtin University, in Perth, Australia, analyzed 54 different studies examining the relationship between light to moderate drinking and health. Of these, only seven did not inappropriately mingle former drinkers and abstainers.

All seven of those studies found no significant differences in the health of those who drank -- or previously drank -- and those who never touched the stuff. The remaining 47 studies represent the body of research that has led to a general scientific consensus that moderate drinking has a health benefit.The Chronical article quotes Dr. Tim Naimi at the Centers for Disease Control as saying "The whole field of 'moderate drinking' studies is deeply flawed" and goes on to say:

In a study published in May 2005 in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine, Naimi and other CDC colleagues found that the comparatively higher risk of heart disease in abstainers could be explained by socioeconomic factors rather than lack of protection from alcohol consumption. Non-drinkers, for example, tended to be poorer than drinkers, had less access to health care, and had less healthy diets.

Note that in the 1988 article, Shaper and his colleagues were also concerned about difference in drinking habits of different groups, in particular manual and non-manual workers.

Naimi says "Anyone who suggests that people should begin drinking, or drink more frequently, to reduce the risk of heart disease is misguided".

DISCUSSION

(1) The chronicle quotes Dr. Arthur Klatsy, a well-known researcher on the benefits of moderate drinking:

There are inherent weaknesses in all the epidemiological studies of alcohol and heart health. What is needed is a randomized trial in which a group is assigned to consume one or two drinks a day and another abstains, and their comparative health is assessed over a period of years.

Do you it would be possible to carry out such a study?