Sandbox: Difference between revisions

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

The following five graphs [http://jnci.oxfordjournals.org/content/102/9/605.full found in an article by Welch and Black] illustrate this conundrum of modern medicine: it can do a great deal of harm precisely because it is so good at doing things such as finding abnormalities which represent non-threatening deviations from what is deemed normal. | The following five graphs [http://jnci.oxfordjournals.org/content/102/9/605.full found in an article by Welch and Black] illustrate this conundrum of modern medicine: it can do a great deal of harm precisely because it is so good at doing things such as finding abnormalities which represent non-threatening deviations from what is deemed normal. | ||

<center>[[File:F7_Overdiagnosis.gif ]]</center> | <center>[[File:F7_Overdiagnosis.gif |500px ]]</center> | ||

Notice that for each of the five cancers, its time series of mortality is flat whereas the number of new diagnoses rises prohibitively over time indicating overdiagnosis and therefore, overtreatment with consequent suffering. | Notice that for each of the five cancers, its time series of mortality is flat whereas the number of new diagnoses rises prohibitively over time indicating overdiagnosis and therefore, overtreatment with consequent suffering. | ||

Revision as of 02:36, 27 February 2014

Some frightening graphs

Most people believe that

- Unless treated, cancer is necessarily fatal; and

- The earlier cancer is diagnosed and treated, the more likely the cure

Because cancer is a catchall term, #1 is certainly wrong. Some cancers grow so slowly that death is due to another cause. Indeed, some cancers are so indolent that a person may lead an entire life unaware even of the existence of the cancer. Therefore, in spite of its plausibility, #2 is suspect because diagnoses based on a screening test might lead to unnecessary and harmful treatments.

The following five graphs found in an article by Welch and Black illustrate this conundrum of modern medicine: it can do a great deal of harm precisely because it is so good at doing things such as finding abnormalities which represent non-threatening deviations from what is deemed normal.

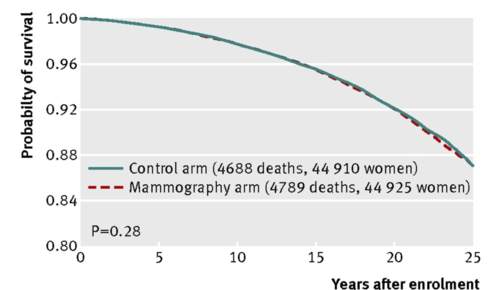

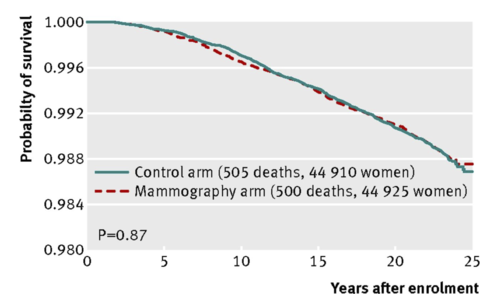

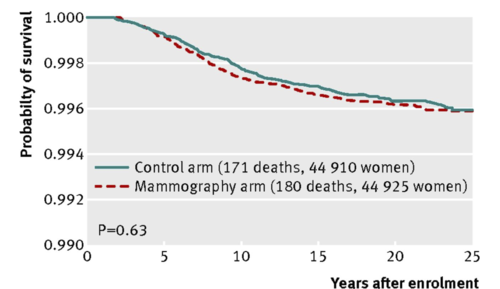

Notice that for each of the five cancers, its time series of mortality is flat whereas the number of new diagnoses rises prohibitively over time indicating overdiagnosis and therefore, overtreatment with consequent suffering. As another instance of overdiagnosis, overtreatment and consequent suffering, the following three figures are taken from an article by Miller, et al, in the British Medical Journal (BMJ 2014;348:g366 doi: 10.1136/bmj.g366), entitled “Twenty five year follow-up for breast cancer incidence and mortality of the Canadian National Breast Screening Study: randomised screening trial.”

This very large--a sample size of approximately 90,000-- 25 year randomized control trial concludes that

Annual mammography in women aged 40-59 does not reduce mortality from breast cancer beyond that of physical examination or usual care when adjuvant therapy for breast cancer is freely available. Overall, 22% (106/484) of screen detected invasive breast cancers were over-diagnosed, representing one over-diagnosed breast cancer for every 424 women who received mammography screening in the trial.

Discussion

1. With regard to the five time series, suppose instead of overdiagnosis and overtreatment, the following (reverse causality) argument is made: despite the rise in each of the cancers, modern medicine has kept the mortality constant. Comment on this assertion.

2. Notice that in the above Figs 2, 3 and 4, a p-value is given for the comparison between the mammography arm and the control arm. Looking at the curves themselves, comment as to why it makes sense that each of the p-values is well above the mystical .05.

3. With regard to the mammography study, there is an accompanying editorial in the BMJ entitled “Too much mammography.” This editorial goes on to compare and contrast PSA screening with mammography. Although PSA screening and mammography seem to be very similar "owing to [the] small effect on mortality and large risk of overdiagnosis ([1]),"

Nevertheless, the UK National Screening Committee does recommend mammography screening for breast cancer but not prostate specific antigen screening for prostate cancer.

Because the scientific rationale to recommend screening or not does not differ noticeably between breast and prostate cancer, political pressure and beliefs might have a role.

We agree with Miller and colleagues that “the rationale for screening by mammography be urgently reassessed by policy makers.” As time goes by we do indeed need more efficient mechanisms to reconsider priorities and recommendations for mammography screening and other medical interventions. This is not an easy task, because governments, research funders, scientists, and medical practitioners may have vested interests in continuing activities that are well established.

Comment on the vested interests and why the task is difficult.

Submitted by Paul Alper