Sandbox: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

Lucky Charms and Disappointing Journalism | |||

The headline of the WSJ article [http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703648304575212361800043460.html The Power of Lucky Charms New Research Suggests How They Really Make Us Perform Better] is eye catching. The descriptions of the success or failure of the lucky charms is, however, an indictment of the way the journalism profession discusses statistics. Especially because the author, Carl Bialik, unlike most journalists, knows better. In fact, while his first paragraph tries to draw the reader in with “Can luck really influence the outcome of events,” his second paragraph begins with “They [lucky charms] do (sometimes)” as a means of absolving himself from taking the material seriously. | |||

In silly instance after silly unreplicated instance, the article tells us that averages improve or don’t improve with lucky charms present, but never once do we know anything about the variability between the charm holders and those deprived of the lucky charms. | |||

'''Discussion Questions''' | |||

Submitted by | 1. The first example referred to will be published in the June issue of Psychological Science; the study involves 28 German college students whose putting with a “lucky ball” sank “6.4 putts out of 10, nearly two more putts, on average, than those who weren’t told the ball was lucky.” Evaluate the comment, “but the effect was big enough to be statistically significant.” What additional statistical information would be necessary to view this study as worthwhile? | ||

2. A well known quotation in the field of statistics is “The plural of anecdote is not evidence.” Read the article and evaluate the anecdotes. | |||

3. Superstition plays a vital part of this article: a motorcyclist who wears “gremlin balls” to “help ward off accidents”; a lucky brown suit “to help the horse he co-owns, Always a Party, win the second race”; after an eclipse, “major U.S. stock-market indexes typically fall.” Compare those superstitions with the reading of tea leaves and goat entrails of the middle ages. | |||

Submitted by Paul Alper | |||

==Tea party graphics== | ==Tea party graphics== | ||

Revision as of 00:47, 30 April 2010

Lucky Charms and Disappointing Journalism

The headline of the WSJ article The Power of Lucky Charms New Research Suggests How They Really Make Us Perform Better is eye catching. The descriptions of the success or failure of the lucky charms is, however, an indictment of the way the journalism profession discusses statistics. Especially because the author, Carl Bialik, unlike most journalists, knows better. In fact, while his first paragraph tries to draw the reader in with “Can luck really influence the outcome of events,” his second paragraph begins with “They [lucky charms] do (sometimes)” as a means of absolving himself from taking the material seriously.

In silly instance after silly unreplicated instance, the article tells us that averages improve or don’t improve with lucky charms present, but never once do we know anything about the variability between the charm holders and those deprived of the lucky charms.

Discussion Questions

1. The first example referred to will be published in the June issue of Psychological Science; the study involves 28 German college students whose putting with a “lucky ball” sank “6.4 putts out of 10, nearly two more putts, on average, than those who weren’t told the ball was lucky.” Evaluate the comment, “but the effect was big enough to be statistically significant.” What additional statistical information would be necessary to view this study as worthwhile?

2. A well known quotation in the field of statistics is “The plural of anecdote is not evidence.” Read the article and evaluate the anecdotes.

3. Superstition plays a vital part of this article: a motorcyclist who wears “gremlin balls” to “help ward off accidents”; a lucky brown suit “to help the horse he co-owns, Always a Party, win the second race”; after an eclipse, “major U.S. stock-market indexes typically fall.” Compare those superstitions with the reading of tea leaves and goat entrails of the middle ages.

Submitted by Paul Alper

Tea party graphics

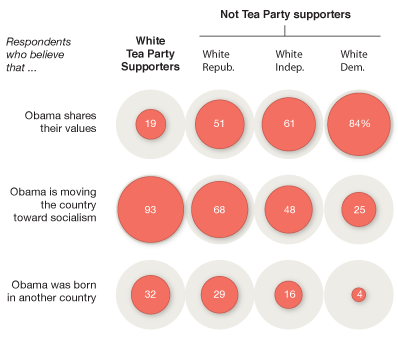

A mighty pale tea

by Charles M. Blow, New York Times, 16 April 2010

This article recounts Blow's experience visiting a Tea Party rally as a self-identified "infiltrator." He was interested in assessing the group's diversity. Reproduced below is a portion of a graphic, entitled The many shades of whites, that accompanied the article.

The data are from a recent NYT/CBS Poll.

Submitted by Paul Alper