Chance News 89: Difference between revisions

| (14 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

October 16, 2012 to November 25, 2012 | |||

==Quotations== | ==Quotations== | ||

"To rephrase Winston Churchill: Polls are the worst form of measuring public opinion — except for all of the others." | "To rephrase Winston Churchill: Polls are the worst form of measuring public opinion — except for all of the others." | ||

| Line 152: | Line 153: | ||

==A forthright stance for uncertainty== | ==A forthright stance for uncertainty== | ||

[http://campaignstops.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/10/30/what-too-close-to-call-really-means/ What Too Close to Call Really Means] by Andrew Gelman, New York Times Campaign Stops blog, October 30, 2012. | [http://campaignstops.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/10/30/what-too-close-to-call-really-means/ What Too Close to Call Really Means] <br> | ||

by Andrew Gelman, ''New York Times'' Campaign Stops blog, October 30, 2012. | |||

You'll probably end up reading this after the election, but a blog entry seven days before the U.S. presidential election elaborates on why Andrew Gelman believes that the race is too close to call and what that really means. | You'll probably end up reading this after the election, but a blog entry seven days before the U.S. presidential election elaborates on why Andrew Gelman believes that the race is too close to call and what that really means. | ||

| Line 184: | Line 186: | ||

Submitted by Steve Simon | Submitted by Steve Simon | ||

=== | ===Last words from Nate Silver=== | ||

While most news organizations continue to repeat that the race is "too close to call", Nate Silver's probabilities for an Obama win continue to climb as Election Day approaches. | While most news organizations continue to repeat that the race is "too close to call", Nate Silver's probabilities for an Obama win continue to climb as Election Day approaches. | ||

His post from Saturday, [http://fivethirtyeight.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/11/03/nov-2-for-romney-to-win-state-polls-must-be-statistically-biased/ Nov. 2: For Romney to win, state polls must be statistically biased], includes the following description for why the race is not a toss-up: | His post from Saturday, [http://fivethirtyeight.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/11/03/nov-2-for-romney-to-win-state-polls-must-be-statistically-biased/ Nov. 2: For Romney to win, state polls must be statistically biased], includes the following description for why the race is not a toss-up: | ||

| Line 198: | Line 200: | ||

==Randomized trials for parachutes== | ==Randomized trials for parachutes== | ||

Paul Alper sent this delightful spoof from the BMJ archives: | |||

[http://www.neonatology.org/pdf/ParachuteUseRPCT.pdf Parachute use to prevent death and major trauma related to gravitational challenge: systematic review of randomised controlled trials], by G.C. Smith GC and J.P. Pell, ''BMJ'', 20 December 2003 | [http://www.neonatology.org/pdf/ParachuteUseRPCT.pdf Parachute use to prevent death and major trauma related to gravitational challenge: systematic review of randomised controlled trials], <br> | ||

by G.C. Smith GC and J.P. Pell, ''BMJ'', 20 December 2003 | |||

The discussion section begins as follows: | |||

<blockquote> | |||

'''Evidence based pride and observational prejudice'''<br> | |||

It is a truth universally acknowledged that a medical intervention justified by observational data must be in want of verification through a randomised controlled trial. | |||

</blockquote> | |||

*"The basis for parachute use is purely observational, and its apparent efficacy could potentially be explained by a ' | Here are some other choice quotations: | ||

*"The basis for parachute use is purely observational, and its apparent efficacy could potentially be explained by a 'healthy cohort' effect." | |||

*"The widespread use of the parachute may just be another example of doctors' obsession with disease prevention and their misplaced belief in unproved technology to provide effective protection against occasional adverse events." | *"The widespread use of the parachute may just be another example of doctors' obsession with disease prevention and their misplaced belief in unproved technology to provide effective protection against occasional adverse events." | ||

| Line 277: | Line 286: | ||

by Andrew Revkin, Dot Earth blog, ''New York Times'', 22 October 2012 | by Andrew Revkin, Dot Earth blog, ''New York Times'', 22 October 2012 | ||

A year ago this fall, New York City received dire warnings about the approaching Hurricane Irene, but actually those of us living in Vermont experienced disastrous flooding. This year, the tables were turned. | A year ago this fall, New York City received dire warnings about the approaching Hurricane Irene, but actually those of us living in Vermont experienced disastrous flooding. This year, the tables were turned. Here in Middlebury, local schools were preemptively cancelled a day in advance of the storm, but we had sunshine the following morning. Meanwhile, as everyone knows, New York City and New Jersey suffered major devastation. | ||

Given such history, Revkin asks: "...when projections are off, can meteorologists be taken to court for needlessly disrupting some people’s lives and for lulling others into a false sense of safety?" As he notes, this is not a purely hypothetical question, given the recent manslaughter convictions of six Italian scientists and a government official for failing to provide adequate warning of the 2009 L'Aquila earthquake | Given such history, Revkin asks: "...when projections are off, can meteorologists be taken to court for needlessly disrupting some people’s lives and for lulling others into a false sense of safety?" As he notes, this is not a purely hypothetical question, given the recent manslaughter convictions of six Italian scientists and a government official for failing to provide adequate warning of the 2009 L'Aquila earthquake. Revkin references an earlier article [http://www.nytimes.com/2011/10/04/science/04quake.html?_r=0 Trial over earthquake in Italy puts focus on probability and panic] (by Henry Fountain, ''New York Times'', October 3, 2011), which appeared as the trial was getting underway. There we read: | ||

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

In the months before a magnitude 6.3 quake hit L’Aquila on April 6, 2009, killing more than 300, the area had experienced an earthquake swarm. That probably increased the likelihood of a major earthquake in the near future by a factor of 100 or 1,000, Dr. Jordan [director of the Southern California Earthquake Center] said, but the probability remained very low — perhaps 1 in 1,000. | In the months before a magnitude 6.3 quake hit L’Aquila on April 6, 2009, killing more than 300, the area had experienced an earthquake swarm. That probably increased the likelihood of a major earthquake in the near future by a factor of 100 or 1,000, Dr. Jordan [director of the Southern California Earthquake Center] said, but the probability remained very low — perhaps 1 in 1,000. | ||

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

The scientists convened a meeting where such estimates were discussed. Unfortunately, in the news conference that followed, | The scientists convened a meeting where such estimates were discussed. Unfortunately, in the news conference that followed, public officials appeared to downplay the risk to avoid panicking the public. The article continues: | ||

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

“The government ended up looking like it was saying, ‘No, there’s not going to be a big earthquake,’ ” when the scientists had not precluded the possibility, said Dr. Jordan, who was the chairman of a commission established by the Italian government after the quake to look at the forecasting issue. | “The government ended up looking like it was saying, ‘No, there’s not going to be a big earthquake,’ ” when the scientists had not precluded the possibility, said Dr. Jordan, who was the chairman of a commission established by the Italian government after the quake to look at the forecasting issue. | ||

| Line 290: | Line 299: | ||

See also the editorial [http://www.nature.com/news/shock-and-law-1.11643 Shock and law] from the journal ''Nature'' (23 October 2012) | See also the editorial [http://www.nature.com/news/shock-and-law-1.11643 Shock and law] from the journal ''Nature'' (23 October 2012) | ||

which also references their [http://www.nature.com/news/2011/110914/full/477264a.html extensive discussion] | which also references their [http://www.nature.com/news/2011/110914/full/477264a.html extensive discussion] | ||

of earthquake science from 2011. While decrying the convictions, the editors are careful to point out the | of earthquake science from 2011. While decrying the convictions, the editors are careful to point out the verdict was not based on the | ||

inability to perfectly predict earthquakes, but rather on the failure | inability of science to perfectly predict earthquakes, but rather on the failure of the panel to adequately inform the public about the risk in advance of the L'Aquila quake. | ||

In light of the other stories in this edition of Chance News, it may be fitting to conclude with this comment by Nate Silver (quoted in [http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/11/11/nate-silver-predictions_n_2114274.html 2012 is the year of Nate Silver and the prediction geeks] ''Huffington Post'', 11 November 2012) : "This is a victory for the stuff (computer modeling) in politics," he said Thursday in a telephone interview. "It doesn't mean we're going to solve world peace with a computer. It doesn't mean we're going to be able predict earthquakes ... but we can chip away at the margins." | In light of the other stories in this edition of Chance News, it may be fitting to conclude with this comment by Nate Silver (quoted in [http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/11/11/nate-silver-predictions_n_2114274.html 2012 is the year of Nate Silver and the prediction geeks] ''Huffington Post'', 11 November 2012) : "This is a victory for the stuff (computer modeling) in politics," he said Thursday in a telephone interview. "It doesn't mean we're going to solve world peace with a computer. It doesn't mean we're going to be able predict earthquakes ... but we can chip away at the margins." | ||

'''Discussion'''<br> | |||

Human intuition is notoriously poor in the face of low probability events with large potential costs. Who is responsible | |||

when failure to comprehend a warning leads to bad outcomes? | |||

Submitted by Bill Peterson | Submitted by Bill Peterson | ||

Latest revision as of 19:13, 18 July 2017

October 16, 2012 to November 25, 2012

Quotations

"To rephrase Winston Churchill: Polls are the worst form of measuring public opinion — except for all of the others."

"If the past is prologue, the polling averages will be off by a few points again this year in many races, but that error may be predictable, at least averaged over many races. And if we could predict the errors, we could do a better job predicting the final margin."

“Scholars at Duke University studied 11,600 forecasts by corporate chief financial officers about how the Standard & Poor's 500 would perform over the next year. The correlation between their estimates and the index was less than zero.”

(posted at ISOSTAT by Tom Moore)

"We found that almost exactly half of the predictions [by the McLaughlin Group TV pundits in 2008] were right, and almost exactly half were wrong, meaning if you'd just flipped a coin instead of listening to these guys and girls, you would have done just as well. …. One of them, actually … said she thought McCain would win by half a point. Of course, what happened the next week where she came back on the air and said, 'Oh, Obama's win had been inevitable, how could he lose with the economy' ... so there's not really a lot of accountability."

“I’m not a fan of including ‘other” in polls, since I never get to pick ‘other’ in real life. There’s no ‘other’ on a menu or my income tax forms. Cops never ask you if you want to take a Breathalyzer, go down to the station or ‘other.’”

“In order to assess the safety of travelling in the Space Shuttle, we could use a method commonly used for other modes of transportation: fatalities per travelled mile. The Shuttle made a lot of miles very safely once in space, and so this method would amount to an infinitesimally small number. However, it would not take into account that there were two distinct time periods in which the Shuttle was a far riskier transport device: the launch and re-entry. The same analogy seems to hold true for SSRIs: they might prevent young people from committing suicide once they are on the drug, but their risk could be increased in the first few weeks when they have just taking their antidepressants.”

“Stephen Senn described statistics as an exporting discipline: we do our job so that others can do theirs.”

Submitted by Margaret Cibes

Forsooth

"Picture yourself behind the wheel on a dark and shadowy night, watching the windshield wipers bat away the rain and wondering, 'What are the odds I’m going to hit a deer?' The answer would be one in 102 if you live in Virginia."

Thanks to Paul Alper for suggesting this story (see more below).

"The main philosophical question is, how should [the recession] be treated? … Should it be treated as an outlier and done away with?"

quoted by Carl Bialik in “Economists’ Goal: A Measure for All Seasons

Submitted by Margaret Cibes

Simpson's paradox on Car Talk

Take Ray out to the ball game...

Car Talk Puzzler, NPR, 22 September 2012

Here is the puzzle: Popeye batted .250 for before the All-Star break, while Bluto batted .300; Popeye batted .375 after the All-Star break, while Bluto batted .400. So how did Popeye win his bet that he would have the better average for the season? Statistically minded listeners will quickly recognize this as an instance of Simpson's Paradox. Still, everything sounds like more fun when Tom and Ray discuss it! You can read their solution here.

A famous real-life example of Simpson's Paradox with batting averages can be found here.

Sleep and fat

Your fat needs sleep, too

by Katherine Harmon, Scientific American, 16 October 2012

As described in the article (actually the transcript from a "60-Second Health" podcast--you can also listen at the link above):

Sleep is good for you. Getting by on too little sleep increases the risk for heart disease, stroke, high blood pressure, diabetes and other illnesses. It also makes it harder to lose weight or stay slim because sleep deprivation makes you hungrier and less likely to be active during the day.

Further,

Now, research shows that sleep also affects fat cells. Our fat cells play an important role in regulating energy use and storage, including insulin processing.

The research referred to, a randomized crossover study, can be found in an article by Josiane Broussard et al. Its full title is “Impaired Insulin Signaling in Human Adipocytes After Experimental Sleep Restriction: A Randomized, Crossover Study.” Scientific American says

For the study, young, healthy, slim subjects spent four nights getting eight and a half hours of sleep and four nights getting only four and a half hours of sleep. The difference in their fat cells was startling: after sleep deprivation, the cells became 30 percent less receptive to insulin signals—a difference that is as large as that between non-diabetic and diabetic patients.

Discussion

1. The Scientific American article fails to mention the number of subjects: “1 woman, 6 men” or two more than the number of authors of the study. The lone female, “participant 6,” had four of her sixteen data points missing.

2. The entire study was carried out at one institution. Why might this be a problem?

3. An extended, positive editorial commentary in the Annals of Internal Medicine refers to Aulus Cornelius Celsus who

argued in favor of “restricted sleep” for the treatment of extra weight…it seems that Celsus may have been wrong: He should have argued in favor of “prolonged sleep” for the treatment of extra weight.

Look up who Celsus is and why his pronouncements about medical matters might be suspect. Then determine why the commentator claims that the authors “deserve commendation for a study that is a valuable [statistically sound] contribution” to the role of sleep in human health.

4. As indicated above, each of the subjects were young, healthy and slim. Why is this uniformity good statistically? For inference purposes to a larger population, why is this uniformity not so good statistically?

Submitted by Paul Alper

Sample size criticized

“Tainted Drug Passed Lab Test”

by Timothy W. Martin et al., The Wall Street Journal, October 24, 2012

A recent meningitis outbreak (24 dead, 312 sick) was linked to a Massachusetts pharmacy that had produced a steroid product which was tested by an independent lab in Oklahoma. On May 25, based on a test designed to detect fungi, the lab reported that the samples were “sterile” and contained a level of endotoxins that was well below the allowable amount.

Some experts have criticized the small sample size – 2 five-ml vials out of 6,528.

In the case of the … steroids tainted with fungi, the size of the testing sample indicated in the Oklahoma lab report—two vials—is much smaller than the standard for the USP test the lab said it was performing. Under the USP standard, for a batch of more than 6,000 vials, the lab should have tested at least 20.

A consultant stated that detection of contamination at a 95% confidence level requires testing of 18% of a batch.

Labs are apparently concerned that the strict testing standards are costly and impractical in some cases. They are calling for looser testing standards.

Only 17 states require that compounding pharmacies follow the U.S. Pharamcopeia guidelines, according to a survey conducted this year by Pharmacy Purchasing & Products, a trade publication.

Question

1. In a perfect textbook world, what sample size would you have chosen - out of a population of 6,528 vials of the proposed drug – to test contamination in this case?

2. Would you be willing to use a smaller sample if cost had been a factor in the testing? if some patients had had a pressing need for the drug?

3. Are there any conditions under which you think it might be appropriate to use a sample size of 2 with respect to testing drugs for contamination?

Submitted by Margaret Cibes

Drivers beware of deer

1-in-80 chance of hitting a deer here

Star Tribune (Minneapolis), 27 October 2012

We read:

Minnesota drivers have a nearly 1-in-80 chance of hitting a deer in the next year, making this the eighth-most likely state for such collisions. Minnesota actually dropped from sixth to eighth in the last year, falling behind Wisconsin, which stayed at No. 7.

The statistics come from an analysis prepared by the State Farm insurance company using Federal Highway Administration data.

South Dakota moved from third to second on the list with 1-in-68 odds. Iowa dropped from No. 2 to No. 3 with 1-in-71.9 chances. West Virginia was No. 1 with odds of 1 in 40.

Given the thousands of motorists, can the deer population really be this high?

Discussion

What do you think this statistic represents? Certainly the Washington Post interpretation (see Forsooth above) is not correct.

Submitted by Paul Alper

Skewered charts

“A History Of Dishonest Fox Charts”, October 1, 2012

Media Matters has compiled a group of two dozen Fox News charts that showcase a number of potentially exaggerated claims about government activities. The charts contain graphical distortions (y-axes not scaled from 0), as well as content distortion (comparisons of apples to oranges). (Note that all viewers might not agree with the critiques, as witness the heated and personal online blog responses.)

Submitted by Margaret Cibes

Birthday wishes

“Social Media Advice: When To Wish Happy Birthday?”,

NPR, All Things Considered, 15 October 2012

The article focuses on the appropriate conditions to wish someone a happy birthday digitally. As part of the lead in, Melissa Block of NPR reports, "Birthdays, they only come once a year. But if you have hundreds, perhaps, even thousands of friends on Facebook, chances are it's someone's birthday every day."

This was not a birthday problem I had heard before. How many people are needed so that the probability that someone has a birthday each day is at least 50%? 23 is not the correct answer to this one. Clearly it is more than 365. In fact, hundreds is not nearly enough. Thousands, however, is.

Question

How is this probability calculated?

Submitted by Chris Andrews

A forthright stance for uncertainty

What Too Close to Call Really Means

by Andrew Gelman, New York Times Campaign Stops blog, October 30, 2012.

You'll probably end up reading this after the election, but a blog entry seven days before the U.S. presidential election elaborates on why Andrew Gelman believes that the race is too close to call and what that really means.

First, Dr. Gelman notes how much people want a direct answer to the question "Who is going to win the election on November 6, Barack Obama or Mitt Romney?"

Different models use different economic and political variables to predict the vote, but these predictions pretty much average to 50-50. People keep wanting me to say that Obama's going to win — I do live near the fabled People's Republic of the Upper West Side, after all — but I keep saying that either side could win. People usually respond to my equivocal non-forecast with a resigned sigh: "I was hoping you’d be able to reassure me."

Different groups provide different probabilities. Nate Silver at the FiveThirtyEight blog at the New York Times placed the probability of an Obama win at 72.9% while the betting service InTrade, places it at 62%. That may sound like a big difference, but

it corresponds to something like a difference of half a percentage point in Obama’s forecast vote share. Put differently, a change in 0.5 percent in the forecast of Obama’s vote share corresponds to a change in a bit more than 10 percent in his probability of winning. Either way, the uncertainty is larger than the best guess at the vote margin.

The whole issue, Dr. Gelman reminds us, is an illustration of how difficult it is to understand probabilities.

My point is that it’s hard to process probabilities that fall between, say, 60 percent and 90 percent. Less than 60 percent, and I think most people would accept the “too close to call” label. More than 90 percent and you’re ready to start planning for the transition team or your second inaugural ball. In between, though, it’s tough.

Dr. Gelman tries to offer a football analogy. An 80% chance of winning is like being ahead in a (U.S.) football game by three points with five minutes left to play and a 90% chance of winning is like being ahead by seven points with five minutes left to play.

Lest you accuse Dr. Gelman of ducking the tough calls, he does note a rather bold prediction he made about the U.S. Congressional elections in 2010.

Let me be clear: I'm not averse to making a strong prediction, when this is warranted by the data. For example, in February 2010, I wrote that "the Democrats are gonna get hammered" in the upcoming congressional elections, as indeed they were. My statement was based on the model of the political scientists Joseph Bafumi, Robert Erikson and Christopher Wlezien, who predicted congressional election voting given generic ballot polling ("If the elections for Congress were being held today, which party’s candidate would you vote for in your Congressional district?"). Their model predicted that the Republicans would win by 8 percentage points (54 percent to 46 percent). That’s the basis of an unambiguous forecast.

Discussion

1. If Mitt Romney wins on November 6, does that invalidate InTrade's estimate of 62% probability of an Obama win? Does it invalidate Nate Silver's estimate of 72.9% probability of a win?

2. Does it make sense to report 72.9% versus 73% (or versus 70%) in Nate Silver's model? In other words, how many digits are reliable: three, two, or one?

3. What is your probability threshold for calling an election "too close to call"?

Submitted by Steve Simon

Last words from Nate Silver

While most news organizations continue to repeat that the race is "too close to call", Nate Silver's probabilities for an Obama win continue to climb as Election Day approaches. His post from Saturday, Nov. 2: For Romney to win, state polls must be statistically biased, includes the following description for why the race is not a toss-up:

Although the fact that Mr. Obama held the lead in so many polls is partly coincidental — there weren’t any polls of North Carolina on Friday, for instance, which is Mr. Romney’s strongest battleground state — they nevertheless represent powerful evidence against the idea that the race is a “tossup.” A tossup race isn’t likely to produce 19 leads for one candidate and one for the other — any more than a fair coin is likely to come up heads 19 times and tails just once in 20 tosses. (The probability of a fair coin doing so is about 1 chance in 50,000.)

If nothing else, it is nice to see a clean description of a p-value!

Discussion

What assumptions underlie this calculation?

Submitted by Bill Peterson

Randomized trials for parachutes

Paul Alper sent this delightful spoof from the BMJ archives:

Parachute use to prevent death and major trauma related to gravitational challenge: systematic review of randomised controlled trials,

by G.C. Smith GC and J.P. Pell, BMJ, 20 December 2003

The discussion section begins as follows:

Evidence based pride and observational prejudice

It is a truth universally acknowledged that a medical intervention justified by observational data must be in want of verification through a randomised controlled trial.

Here are some other choice quotations:

- "The basis for parachute use is purely observational, and its apparent efficacy could potentially be explained by a 'healthy cohort' effect."

- "The widespread use of the parachute may just be another example of doctors' obsession with disease prevention and their misplaced belief in unproved technology to provide effective protection against occasional adverse events."

- "The perception that parachutes are a successful intervention is based largely on anecdotal evidence...We therefore undertook a systematic review of randomised controlled trials of parachutes...Our search strategy did not find any randomised controlled trials of parachutes."

- "We feel assured that those who advocate evidence based medicine and criticise use of interventions that lack an evidence base will not hesitate to demonstrate their commitment by volunteering for a double blind, randomised placebo controlled, crossover trial."

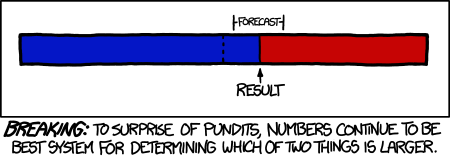

Election wrap-up: Statisticians vs. pundits

Now that the election is over, how did all the forecasts pan out? Jeff Witmer posted the following comic from XKCD on the Isolated Statisiticians list:

Margaret Cibes sent the following before and after comments on the pundits:

- “‘Gut.’ ‘Momentum.’ ‘Who knows?’ ‘Maybe.’ Every word of that carefully hedged, adding up to a giant nothing-burger. But these are the kinds of analyses that earn you pundit cred. They're ‘smart takes.’ Meanwhile Nate Silver is being raked over the coals for committing the sin of showing his math.”

- “Some of the guys who show up on TV … disagree not only with Silver's conclusions, but apparently also with the idea that a statistical model could tell us anything at all about an election. …. Well, look, you can see his record for yourself: 50 for 50.”

(posted by G. Jay Kerns on the Isolated Statisiticians list)

Also from Margaret: this link to a 5-minute video of Nate Silver on the Colbert Report (November 5, 2012).

Paul Alper sent this story, Pundit accountability: The official 2012 election prediction thread, Washington Post (5 November, 2012), which compiles predictions (with links) from a wide variety of sources, including statisticians, pundits and political consultants. For those keeping score at home, as the sports announcers say!

On the New York Times Campaign Stops blog, Timothy Egan sums it up this way in Revenge of the polling nerds (7 November 2012):

This was the year the meta-analyst shoved aside the old-school pundit. Simon Jackman of Stanford, Sam Wang at the Princeton Election Consortium and, of course, our colleague Nate Silver, all perfected math-based, non-subjective models that produced predictions that closely matched the outcomes.

People who are surprised by the election...were probably listening to people who are paid to fantasize.

Visualization

“Amanda Cox”, Significance, October 2012

The magazine's editor interviews the winner of ASA’s 2012 award for excellence in statistical reporting. Cox is graphics editor at The New York Times, where her work is focused on visualization of information.

Readers are referred to another interview with Ms. Cox[1] at the website Simply Statistics, a blog “posting ideas we find interesting, contributing to discussion of science/popular writing, linking to articles that inspire us, and sharing advice with up-and-coming statisticians.” (Cox says here that she uses R for her sketches.)

Readers might also consult a new book, Visualizing Time: Designing Graphical Representations for Statistical Data, by the visualization architect and principal software engineer for SPSS (Springer, 2012).

Statistics/mathematics students may find the interviews especially interesting, as Cox appears to be closer to their age than most other accomplished people they read about.

Submitted by Margaret Cibes

Questioning media reports

“Score and ignore: A radio listener’s guide to ignoring health stories”

by Kevin McConway and David Spiegelhalter, Significance, October 2012

The authors suggest a checklist of 12 questions to ask about the report of a health study, ordered to form an acronym of the name of a BBC radio host:

J = Just observing people?

O = Original information unavailable?

H = Headline exaggerated?

N = No independent comment?

H = “Higher risk”?

U = Unjustified advice?

M = Might be explained by something else?

P = Public relations puff?

H = Half the picture?

R = Relevance unclear?

Y = Yet another single study?

S = Small?

Listeners are asked to score one point for each “yes” answer. The higher the total score, the less “usefulness of the story to a reader as a source of reliable information relevant to their [sic] own health.”

The authors also refer readers to Health News Review, which rates health news stories on ten criteria.

Submitted by Margaret Cibes

The perils of failed predictions

Italy’s troubling earthquake convictions

by Andrew Revkin, Dot Earth blog, New York Times, 22 October 2012

A year ago this fall, New York City received dire warnings about the approaching Hurricane Irene, but actually those of us living in Vermont experienced disastrous flooding. This year, the tables were turned. Here in Middlebury, local schools were preemptively cancelled a day in advance of the storm, but we had sunshine the following morning. Meanwhile, as everyone knows, New York City and New Jersey suffered major devastation.

Given such history, Revkin asks: "...when projections are off, can meteorologists be taken to court for needlessly disrupting some people’s lives and for lulling others into a false sense of safety?" As he notes, this is not a purely hypothetical question, given the recent manslaughter convictions of six Italian scientists and a government official for failing to provide adequate warning of the 2009 L'Aquila earthquake. Revkin references an earlier article Trial over earthquake in Italy puts focus on probability and panic (by Henry Fountain, New York Times, October 3, 2011), which appeared as the trial was getting underway. There we read:

In the months before a magnitude 6.3 quake hit L’Aquila on April 6, 2009, killing more than 300, the area had experienced an earthquake swarm. That probably increased the likelihood of a major earthquake in the near future by a factor of 100 or 1,000, Dr. Jordan [director of the Southern California Earthquake Center] said, but the probability remained very low — perhaps 1 in 1,000.

The scientists convened a meeting where such estimates were discussed. Unfortunately, in the news conference that followed, public officials appeared to downplay the risk to avoid panicking the public. The article continues:

“The government ended up looking like it was saying, ‘No, there’s not going to be a big earthquake,’ ” when the scientists had not precluded the possibility, said Dr. Jordan, who was the chairman of a commission established by the Italian government after the quake to look at the forecasting issue.

See also the editorial Shock and law from the journal Nature (23 October 2012) which also references their extensive discussion of earthquake science from 2011. While decrying the convictions, the editors are careful to point out the verdict was not based on the inability of science to perfectly predict earthquakes, but rather on the failure of the panel to adequately inform the public about the risk in advance of the L'Aquila quake.

In light of the other stories in this edition of Chance News, it may be fitting to conclude with this comment by Nate Silver (quoted in 2012 is the year of Nate Silver and the prediction geeks Huffington Post, 11 November 2012) : "This is a victory for the stuff (computer modeling) in politics," he said Thursday in a telephone interview. "It doesn't mean we're going to solve world peace with a computer. It doesn't mean we're going to be able predict earthquakes ... but we can chip away at the margins."

Discussion

Human intuition is notoriously poor in the face of low probability events with large potential costs. Who is responsible

when failure to comprehend a warning leads to bad outcomes?

Submitted by Bill Peterson